I write historical fiction about events in history with which I feel a strong connection. I work to understand how and why people acted as they did – to delve into life as it was then for ordinary people. My current books are set in sixteenth century Scotland and Europe at the tail end of the Renaissance and during the Reformation and Counter Reformation, the Tudor period in England – Stuart period in Scotland – and my fictional characters interact with well known people who lived then.

In writing I research the period thoroughly and aim to follow the real historical events which my characters find themselves caught up in as accurately as possible. Many of the events I explore have resulted in who we are today and I find that fascinating. I hope you will too….. more about how I came to write The Seton Chronicles can be found here.

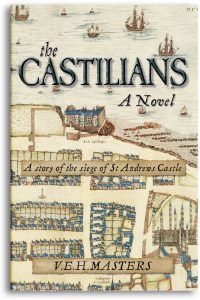

1546 and Scotland is under attack from Henry VIII, determined to marry his son to the infant Mary, Queen of Scots. A few among the Scottish lairds are eager for this alliance too. They kill Cardinal Beaton, who is Mary’s great protector, and take St Andrews Castle, expecting rescue any day from England….read more

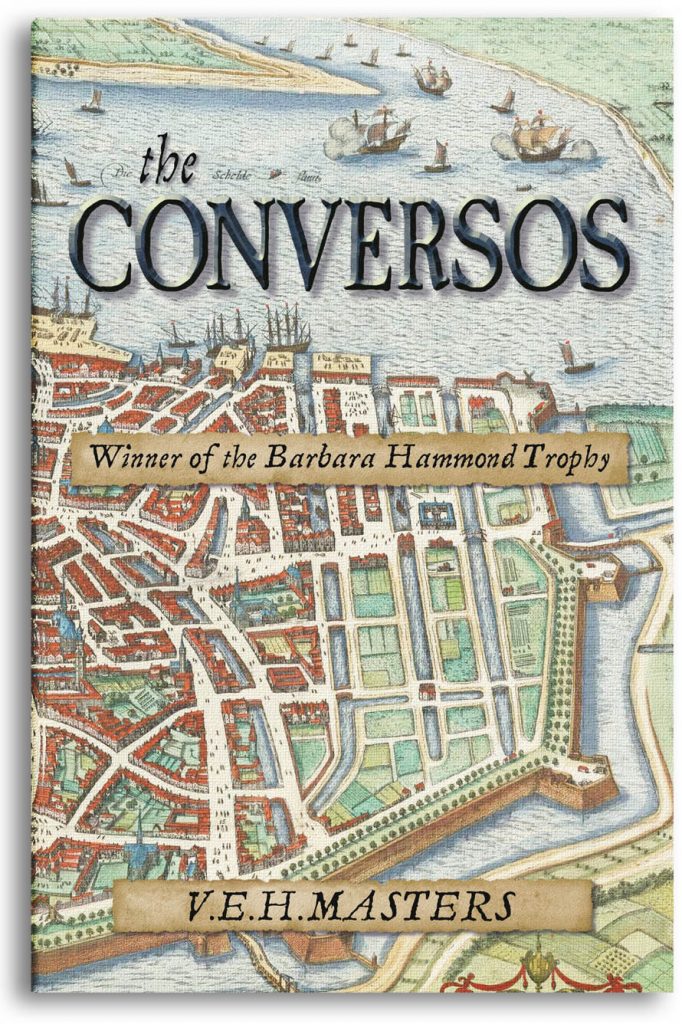

Europe 1547. The rising tide of the Reformation threatens bloody revolution. And the terror of the Inquisition grows, even for those who have converted….read more

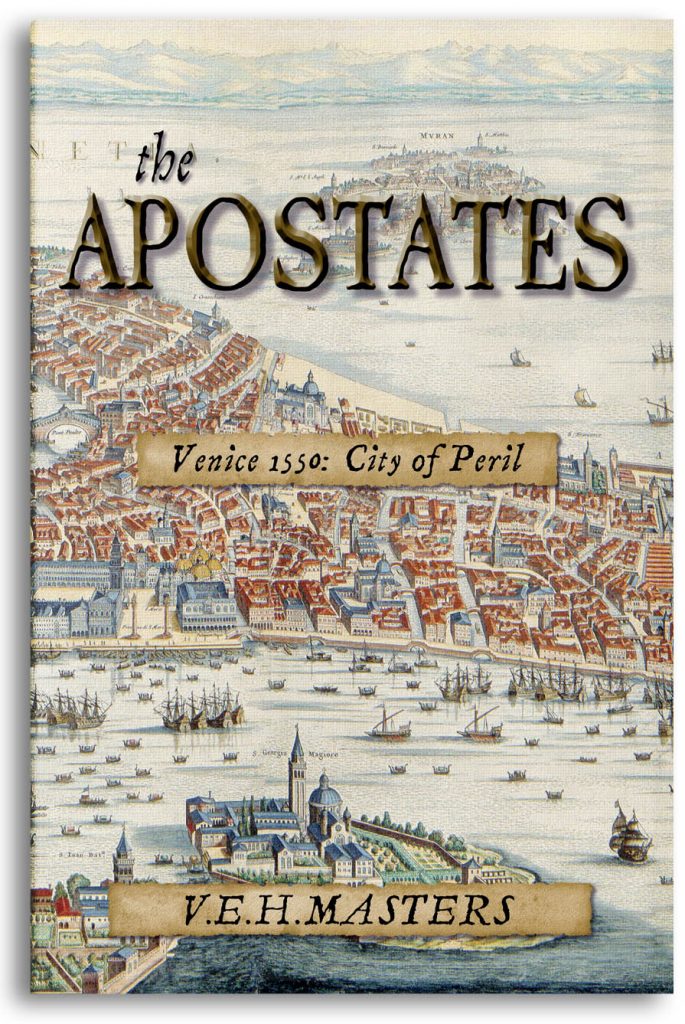

It’s 1550 and Bethia has fled Antwerp, with her infant son, before the jaws of the inquisition clamp down, for the family are accused of secret judaising. She believes they’ve evaded capture but her husband, Mainard, unbeknownst to her, is caught, imprisoned and alone….read more

Italy 1555. Bethia and her growing family find themselves in the midst of the Inquisition’s vicious attack on Jews and Conversos. Despite Bethia’s commitment to her Catholic faith, her greater loyalty to her Converso husband forces them to flee onwards to Constantinople – but will it be any safer?….read more

For a gift of a free copy of my award winning short story A Bonny Lass plus two other shorts stories, which all tell more of about some of the characters in The Seton Chronicles, please go to the newsletter page .

Recent Blogs

- Romanticising Scotland: the impact of Historical Fiction on a Nation #historicalfiction #walterscott #outlanderCulross is a very pretty village set on the opposite of the Firth of Forth to Edinburgh and one of the locations used to film the Outlander series. Sitting in a café there I got chatting to a …

- Murder at the Palace #Historical Fiction #Mary Queen of Scots #ReformationSited at the other end of the Royal Mile to Edinburgh Castle stands Holyrood Palace, built next to what was once an Augustinian monastery, and the site of one the most terrifying events of Mary Queen of Scots …

Continue reading “Murder at the Palace #Historical Fiction #Mary Queen of Scots #Reformation”

- What a good Editor doesMargaret Atwood describes a good copy editor as ‘the person who will save you from yourself,’ and I have to agree. I am fortunate to have Richard Sheehan as mine. After he emerged from editing my most recent in series The Familists I asked him if he would share some of his secrets in a guest post, which he generously agreed to do.