Columbus, despite being unusually learned about cartography when he set sail for the Americas, was convinced he would arrive in Asia. And even after he’d made landfall in the Caribbean he still believed he was near India.

‘Ten journeys away is the river Ganges,’ he wrote in 1503 when he was in what is now known as Guatemala. And when he reached Cuba soon after he believed they were almost upon Cathay.

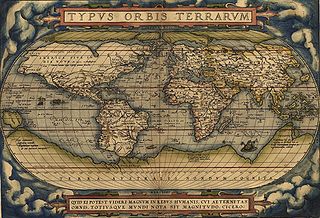

Barely fifty years later the great era of map making was at its zenith and in 1570 the most successful book of the century Theatre of the countries of the world was published in the then most powerful city of the western world, Antwerp. The world’s first ever atlas went through numerous printings (including a pocket edition) and was translated into several languages.

Ortelius, the creator of the first atlas, started out as a map colourist, a profession which I have my character Mainard eager to follow in The Conversos. To become a colourist required not only training but acceptance into the appropriate guild, in this case the Guild of St Luke which admitted sculptors, engravers and printers as well as painters.

What Ortelius did, in creating his Theatrum, was to bring together the work of a number of cartographers with careful attention to making sure their work was as accurate as possible and based on the best sources available. He made several visits to Italy (Venice and Rome were great centres of mapmaking) and attended the Book Fairs in Frankfurt (whose famous fairs began in 1445 and were unsurpassed even then) to source the work.

Ortelius met the geographer Gerard Mercator while they were both attending the Frankfurt Book Fair of 1554 and they became great friends. Mercator did not live in Antwerp, which would perhaps have been expected since it was the centre of printing, but in a small town in Germany. He had previously lived within the Hapsburg realm but, after being arrested for the foul crime of “Luthery” (being a follower of Luther), he fled from the Catholic country as soon as he was released. Those arrested with him were not so fortunate: one man was decapitated; two were burned at the stake; and two women were buried alive.

‘How we see the world depends on what we believe it to be,’ writes Paul Binding of Ortelius, and others, in his book about the making of the first atlas, Imagined Corners. The great “discovery” of the Americas tested Christian Europe – for how could such sophisticated societies as the Aztecs have flourished without knowledge of, and belief in, God. Mercator rationalised it by deciding that biblical writers knew all about these lands and Ortelius decorated his Theatrum with many classical references to Pliny, Plato etc… who ‘got their measurements of the world right.’

The great non Christian cultures of the “New World” were accorded no respect for their achievements in mathematics and astronomy, their genius in urban planning and engineering nor their art and music and were destroyed by a Europe in which, as Binding writes… ‘in their brutal actions against it can one not read an emotional resentment born of so radical a challenge to their identity?’

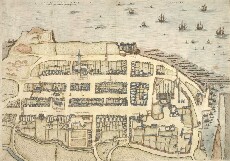

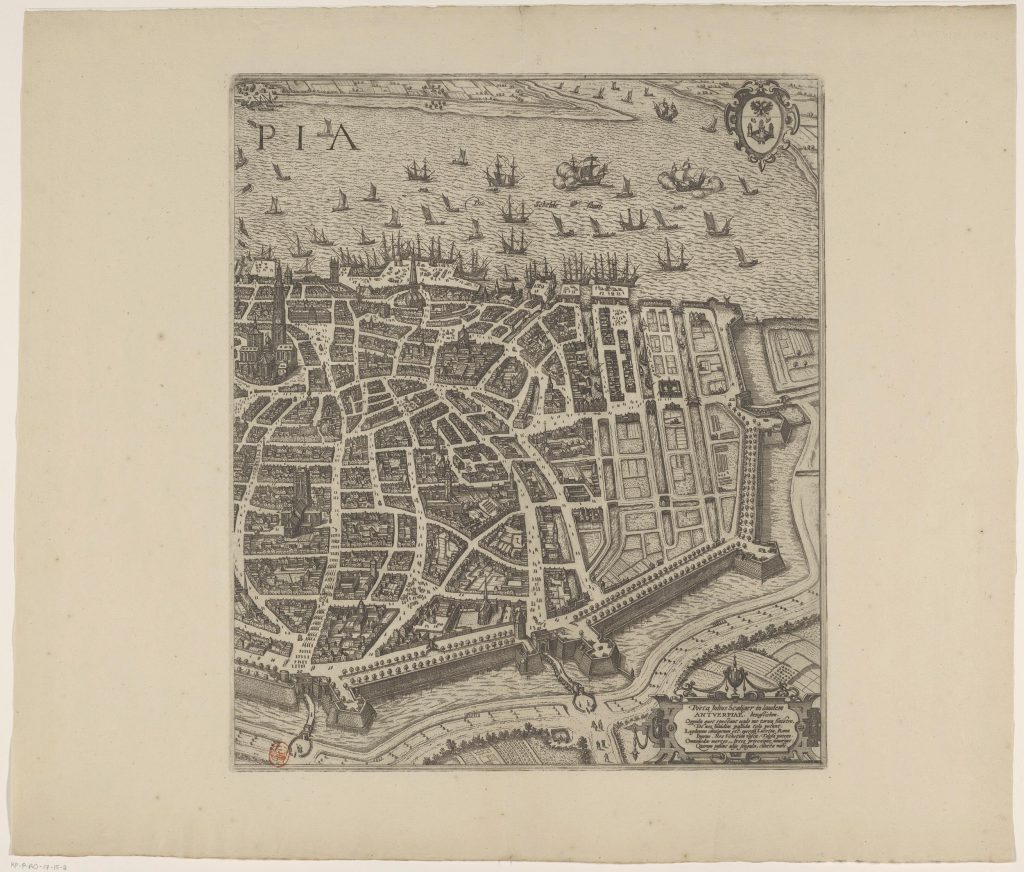

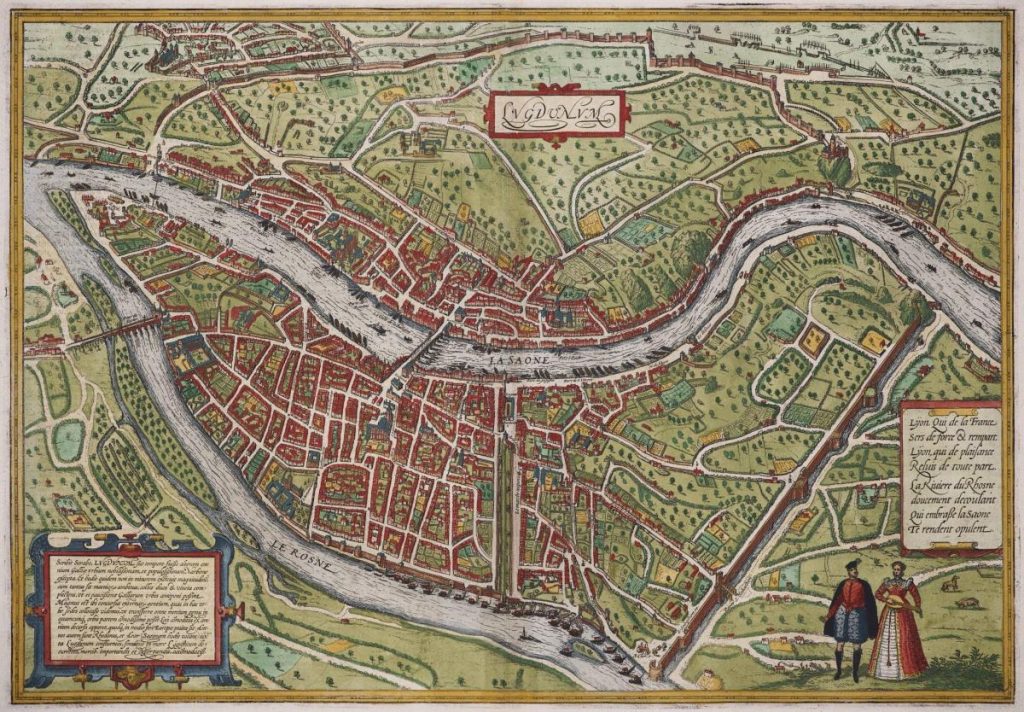

In the later 1500s it became fashionable for the well-to-do to display large scale maps on their walls and the demand for cartography of each city grew. Not only do the maps produced of St Andrews, Antwerp and Venice make beautiful covers for my three books The Castilians, The Conversos and The Apostates, they have also helped me better understand the world my characters inhabit.

For example, in St Andrews the only high walls encircle the grounds of its cathedral (and still do). The city gates are much more about controlling trade than protecting its citizenry from attack, for the guilds were very powerful.

Antwerp, on the other hand, has massive fortifications and the canals encircling it were more about protection than easy movement of goods.

Here’s a map of Lyon from the same era which shows how building in the bend of the river created a defensive barrier on three sides of the city. In The Apostates Bethia and Will find themselves enticed to Lyon where Bethia has an encounter with astrologer, physician and seer, Nostradamus.

And of course we have Venice where The Apostates is in part set, which is again all about trade and easy access for the many galleasses and other smaller craft.

My most recent in series The Apostates is out now and, I’m delighted to say, selling well. Here’s a lovely review from bestselling author, Mercedes Rochelle

‘Beautifully illustrates the religious strife of the period‘

In this volume, we continue the travels of Bethia and Mainard (and their growing family). It’s beginning to look like there isn’t a safe place in Europe for these religious outcasts. Neither Catholic nor Jewish, the Conversos are rejected by both, and Bethia is tainted by association with her new family…

Poor Bethia’s world seems to constrict all around her, though she initially finds solace in Venice, which still leans toward veneration of the Virgin Mary, giving her comfort. But before long, the old persecutions are rearing their ugly heads in Venice as well. The author depicts the fears and frustrations of the Conversos very effectively. I was easily able to identify with their paranoia:

Then one day da Molina came to warn Mainard that the family were under suspicion. Katheline’s activities were not so secret after all. And there were questions about Papa’s burial. Neighbours had reported the unnatural speed with which he was interred and even worse that the corpse was wrapped in white linen – a most foreign and unchristian act. The sense of being constantly watched grew until Bethia was glancing all around whenever she left home.

At the same time, Bethia’s brother Will has gone back to Calvin and trains to be a preacher, himself. So now she has something else to worry about. The Protestants are beset with internal fighting between Calvin and the heretic Servetus, and although this is all in the background, it serves to illustrate even more religious strife in the period. There is no safe place for Bethia to raise her family, and it’s a wonder she is able to hold body and soul together. As a character she is amazingly resilient, and provides the anchor for the reader to hang onto.

The Apostates is available on Amazon UK and Amazon US , and other Amazon sites.

If you want to be kept up to date with new releases, free short stories and other tales of The Seton Chronicles you can subscribe to my monthly newsletter here.