The Impact of frequent changes of religion in Tudor England – Guest Post by Jonathan Posner.

As a writer of historical fiction set in Tudor England, I recognise that religion was the key driver of almost every part of life – and therefore every story – set in the period. Belief in God was fundamental to how society operated, which meant that the doctrinal divisions of Protestant versus Catholic were themselves the primary source of conflict. So it has been very important for me to research and understand these divisions as the background to my action adventure stories.

Why? Because setting my stories in the reign of Elizabeth I allowed me to position a Catholic as an easy enemy. But is that simply too one-dimensional? While it is convenient to demonise the Catholics of the period, I believe it is also necessary to understand their background and motives.

The Tudor era was a period of massive change and upheaval in the religious life of England. Until this time Catholicism had largely been the unchallenged doctrine, with the Pope in Rome as the head of the Church (I say ‘largely’ because the Protestant movement did not start with Martin Luther in 1517 – philosophers like John Wycliffe had challenged the precepts of Catholicism as early as the 14th Century).

But by 1603 everything had changed. The state-sanctioned doctrine was Protestantism, the head of the Church was the monarch, and Catholicism was seen as both heretical and traitorous.

It had not simply been a linear change; there had been a number of reversals along the way – all of which must have been both deeply challenging and destabilising for the majority of men and women of the time.

Let’s take an example. Meet ‘John’. He’s an educated land-owning Englishman, born in 1500 and therefore baptised a Catholic. By the time of his death at the age of 75, he would have seen his faith state-approved, then de-legitimised, then restored, then completely outlawed. So what caused these changes, and what would it have been like for him?

We start with the period leading up to the English Reformation, which was when Henry VIII broke away from Rome in order to marry his second wife, Anne Boleyn. John would, like everyone else, have been secure in his Catholic faith. As a young man he might have heard of the ‘heretical’ teachings of Martin Luther in Germany and John Calvin in Switzerland – but he would have been fairly well insulated from these. His religion came from the priest, who took it from a Latin bible and interpreted it for John and his family in church. The Mass was heard in Latin and the principle was that salvation (from eternal damnation in hell) came from following the Catholic teachings and doing good works. The doctrine of Transubstantiation was also fundamental – that the bread and wine of the Eucharist became the actual body and blood of Christ.

The English Reformation, when viewed through the lens of history and the subsequent rise of Protestantism, could be thought of as changing these services and the practice of faith. But the truth is that very little changed for John and men like him. The Reformation was simply a political and administrative change at the top, replacing the Pope with the King as the head of the Church. England remained Catholic in practice, and Henry ultimately opposed the Bible in English, as he shared the Catholic concern that the common man shouldn’t read it for himself, in case this caused dissent.

But I think it is fair to say that by creating the Church of England, Henry opened the door to the eventual introduction of Protestantism. Luther and Calvin’s teachings were becoming more widely disseminated across Europe. They had also reached England, where they were taken up by many intellectuals, such as leading thinkers like Katherine Parr, Henry’s sixth wife.

She was instrumental in bringing up Henry’s son and heir Edward according to the new doctrine, and Edward also had a fiercely anti-Catholic tutor called Richard Cox. So when Edward ascended the throne in 1547, even as a boy of nine, he was staunchly Protestant. His regents – first his uncle the Duke of Somerset, then the Duke of Northumberland – both supported his Protestant faith. And when Thomas Cranmer, the Archbishop of Canterbury, mandated the English Bible and introduced a new English Book of Common Prayer, Protestantism was truly established.

So our John – now in his late 40s with a wife and children – found that he was expected to reject all he had known and fully accept the new Protestantism. Not only was he told that simply believing in Jesus was enough to ensure his salvation, but he was also expected to have an English Bible and read it to his family. He now had to hear the Mass in English, and to reject the doctrine of Transubstantiation. The reason? In the Protestant doctrine, the bread and wine were now only ‘metaphorical representations’ of the body and blood of Christ.

Imagine how difficult all this would have been for John. Not only did he have to embrace a whole new way of thinking, but there was also a potentially terrifying question to face: what would rejection of his Catholic beliefs do to his immortal soul after death? Would he have to face eternal damnation in hell?

So I am sure that when Edward died in 1553 and his sister Mary I took the throne, John would have been relieved that his Catholicism was to be restored in the Counter Reformation. Mary was determined to reverse the reforms, and had Cranmer and other leading Protestants like Latimer and Ridley burned to death. However, she found many of the changes were harder to undo. The ecclesiastical properties confiscated or sold by Henry were now in the hands of powerful private landowners. These men therefore had a vested interest in preserving the new status quo and opposing any return of their lands, and by association, any return to Catholicism.

Another factor was the appeal of Protestantism to the wider population, with its accessible services and English Bible. While I have assumed our man John remained a Catholic at heart, many of his fellow Englishmen had fully embraced the new faith, and were supported by extensive printed propaganda produced by a strong underground reform movement.

The main problem for Mary was that she only reigned for five years. Even though Protestantism was still new and therefore may have rested on shaky foundations, she didn’t have enough time to turn it around (or even to restore Papal Supremacy).

Then, in 1558, Mary’s half-sister Elizabeth I came to power. As a Protestant, she was determined to undo all Mary’s Catholic changes. Elizabeth had two key reasons for being a Protestant; her mother Anne Boleyn had been a reformist, and Elizabeth had also been brought up by Katherine Parr. So the new Queen set out to restore her late brother’s reforms.

It was fairly straightforward for Elizabeth to implement the Religious Settlement that reinstated Protestantism; between 1559 and 1663 she introduced a number of changes – such as the Thirty Nine Articles that codified the doctrines of the Church of England and the Act of Uniformity that restored Cranmer’s Book of Common Prayer. Together these meant that the Reformation, started by her father and advanced by her brother, had effectively been completed.

What, then, of John? Now in his early 60s, he had a choice to make. Should he continue as a Catholic, but in secret and at risk to himself and his family? Or should he embrace the reformed faith and stay within the Elizabethan state and ecclesiastical laws? And whatever his choice, what would be the risk to his immortal soul?

It would have been a difficult decision, and I do understand if he opted to remain a Catholic. Initially this would not have been too risky, as Elizabeth took a tolerant position. She is understood to have said ‘I will not make windows into men’s souls’. While she professed to be against the practice of Catholicism, she supported her Catholic subjects, provided that they made no trouble.

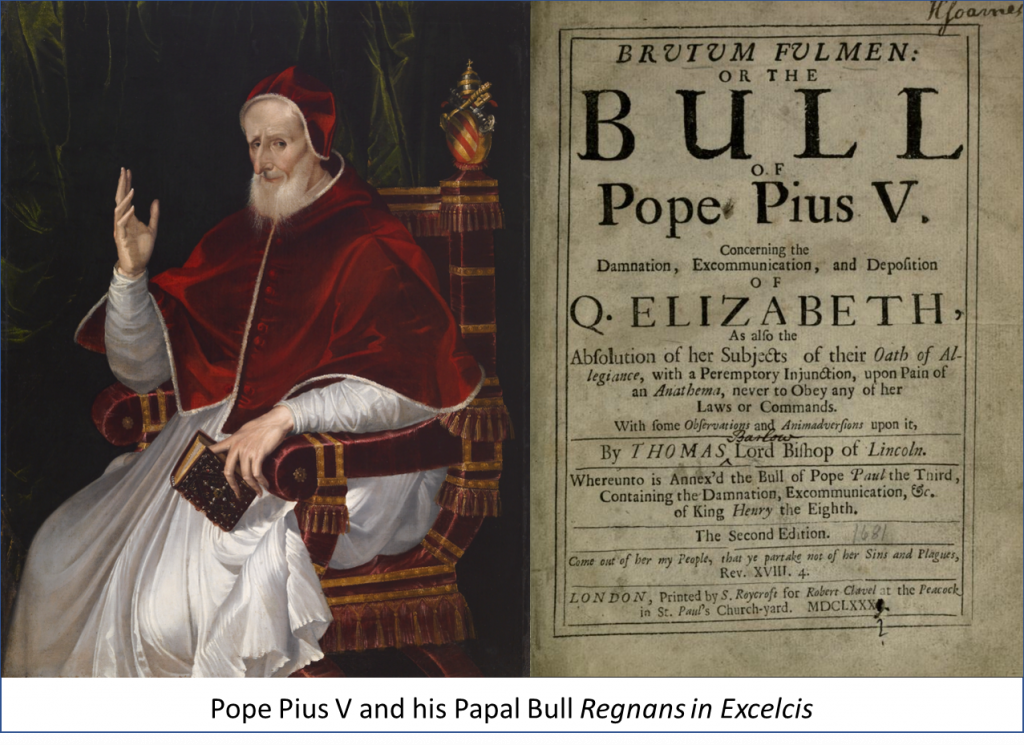

But in 1570 everything changed. Pope Pius V issued a Papal Bull called Regnans in Excelcis; a proclamation which declared Elizabeth to be a heretic and usurper.

Pope Pius made it every Catholic’s duty not only to disobey Elizabeth, but actively to seek her death. Not surprisingly for Elizabeth, this turned every Catholic into a potential traitor, and encouraged a succession of Catholic plots to put her cousin Mary Queen of Scots on the throne. All of these plots were foiled by Elizabeth’s chief spymaster Francis Walsingham, and Mary was eventually executed in 1587.

Would the Papal Bull have been the final straw for John? For the last five years of his life, would he have decided to give in, and embrace the Protestant faith outwardly in public? And who knows, maybe also inwardly in his heart?

Either way, this would have been the final time he had to choose which faith to follow in a long life of such difficult choices.

Jonathan’s latest book The Lawyer’s Legacy is available now for pre-order on Amazon and on Amazon uk.

It’s 1535, and young Robert Wychwoode has his life all planned out – he’s going to become a successful lawyer, fighting for truth and justice. And when he falls for a beautiful young girl, he naturally amends his plans to include her as well. But together they are caught up in a violent plot to overthrow the King and Robert has to decide if he is prepared to compromise his ideals if he’s going to foil the plot – and save the life of the girl he loves.