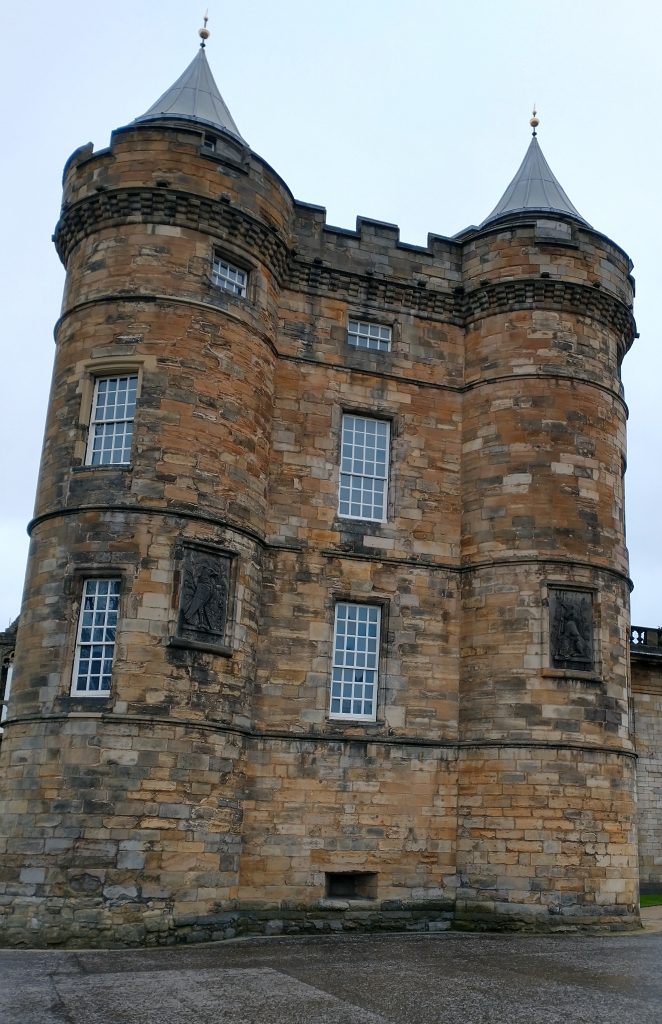

Sited at the other end of the Royal Mile to Edinburgh Castle stands Holyrood Palace, built next to what was once an Augustinian monastery, and the site of one the most terrifying events of Mary Queen of Scots life, during her brief reign.

In the 1500s, when my characters in The Seton Chronicles were alive the palace stood outside the city walls. It has been extended and refashioned over the centuries so what was there then was considerably smaller.

In 1548 the five year old Mary was betrothed to the Dauphin and left for France. I write of her journey in my second in series, The Conversos (see below for a short extract)

It was a miracle Mary arrived in France safely for the ship was beset by storms and a voyage which would normally take five days took eighteen, with weather in August worthy of the worst of January. It was said that Scotland didn’t want to let her queen go.

She had a happy life in France and her future father-in-law, King Henri II, was fond of her. She returned to Scotland in 1561, aged nineteen, dressed in white – the shade of mourning – because her husband, father-in-law and mother had all died within a year of one another. And she came from the luxury and warmth of Renaissance France to a bleak and chilly Scotland.

The chambers in Holyrood were dull, dreary and comfortless but Mary didn’t travel light. She brought with her 45 beds, 5 canopies, 20 coverings and 20 bolts of tapestry, plus paintings, jewellery and furnishings. All of which was taken south by James VI when Queen Elizabeth I died and he became King of England, Ireland and Wales, as well as Scotland.

Mary made the best of things which wasn’t easy as a Catholic in a now Protestant Scotland. She was naturally drawn to people who shared her faith and love of music. David Rizzio, an Italian became her secretary and close companion. Starved of the entertainment she’d enjoyed in France and in an austere Reformation Scotland where singing and dancing were frowned upon and the Reformer John Knox openly castigated her, indeed had her in tears for so indulging, Rizzio must have been a welcome reminder of her life in France.

He was unpopular with many of the courtiers who surrounded her, as a foreigner who had too much influence over her. One night she was having a meal in the small supper room off her bed chamber with Rizzio and a number of her ladies when a large group of men burst in, including Mary’s husband Lord Darnley.

Mary was six months pregnant at the time and there were rumours spread that Rizzio was the father of her unborn child. The men pushed past her and dragged Rizzio into the outer bedchamber where he was butchered in front of her.

David Rizzio was stabbed fifty four times with Lord Darnley taking a lead in the attack. His blood stains the floor still – although I suspect it may have been occasionally re-reddened over the subsequent centuries because it looked remarkably bright when I recently visited the palace.

Mary gave birth a few months later, not in Holyrood but in a small chamber in Edinburgh Castle with a number of men watching to verify the birth of the future monarch. Darnley was called to see his new son, who would become James VI, and gazed down upon him as Mary held him in her arms

“My Lord,’ she said, ‘God has given me a son begotten by none other but you.’

Darnley blushed, one would hope shamed by the accusation he’d made of Mary’s adultery, and bent to kiss his son. She never forgave Darnley for Rizzio’s murder and when Darnley was himself murdered a few months later, she was held partly responsible. He was a vile man and here’s a retelling of a quarrel he had with Mary over dinner during a stay at Traquair House shortly after their son’s birth, and as reported by its owner.

Mary, who was feeling unwell, whispered in her husband’s ear she thought she may have been pregnant again and could she be excused from the stag hunt the following day. Darnley rudely replied:

“Never mind, if we lose this one, we can make another!”

The Laird rebuked him sharply and said he did not speak like a Christian whereupon Darnley replied:

“What! Ought not we to work a mare well when she is with foal?”

Holyrood Palace fell into disuse once Mary’s son James became king of England and removed there. By the 1800s, with the popularity of Sir Walter Scott novels, Scotland became a place for those with romantic sensibilities to visit, and the story of Mary Queen of Scots especially drew visitors to Holyrood Palace.

In the first year it was opened to the public 67,000 people visited and they had to fence off her bed to stop people touching it. But of course it was not her actual bed and when Sir Walter Scott stage managed King George IV’s successful visit to Scotland the dilapidated bed was at least replaced by one of red damask, perpetuating the romanticism. Indeed there is nothing left of Mary’s time in Holyrood apart from the audience room ceiling which was commissioned by her mother Mary of Guise, to celebrate Mary’s alliance with France and the joining of the Scottish and French Royal Houses – and, of course, David Riccio’s blood stains.

Here’s the short extract from The Conversos describing Mary’s voyage to France aged five:

The child hangs back, tugging on the hand which is pulling her forward. The wind blows her cloak and veil in a great swirl around her small body. What are they thinking of, to bring such a precious cargo out in a rowboat on a day like this?. His shackle companion nudges Will, inquiring, in Spanish, if this is indeed the wee queen. Will thinks before responding, then shrugs. It doesn’t matter if the man knows.

Eventually courtiers, ladies-in-waiting, soldiers, and small children are all uploaded. It’s early evening, and although it won’t be dark for many hours, a decision has clearly been made to set sail in the morning. Will has nodded off over his oar when he becomes aware the bosun’s chair is being prepared again, and up comes the Dowager Queen Marie. She is a tall sturdy woman with a firm line to her mouth, indicating great determination, but the worry lines across her high plucked forehead give a sense of the cost of such determination.

A small child bursts from a forward cabin, chased by her ladies. ‘Maman, maman,’ she calls. ‘Venez-vous avec moi?’ The last is said with such hopefulness that Will feels a lump in his throat and wonders what is wrong with him to be so sentimental about a Catholic monarch, albeit a small child.

The queen mother shakes her head but gathers the child to her and disappears into the cabin.

The two ladies-in-waiting stay out on deck, and Will, whose position is nearby, catches snippets of their conversation. ‘This is not wise…. the queen was settling… now we must deal with her distress once more.’

The queen mother emerges, face impassive. ‘She’s asleep now, you may go to her.’

Logie comes, bows low over her hand and escorts her to the ship’s side. ‘I will take very good care of our queen,’ he promises. She doesn’t speak but taps his arm in acknowledgement. She’s swung out, and after a few moments Will sees her rowed over to the ship on which she arrived.

Logie comes to lean on the railing nearby. ‘It is very sad,’ he says. ‘Who knows when, or if, our dowager queen will see her only, and much loved, child again.’

He is called away before Will can reply. Will sits unmoving as the dusk falls, feeling weary with sadness. Who knows when any of us may see our loved ones again, he thinks. But still his heart is wrung with pity for the wee queen hounded from one side of her country to the other because of her marriageability.

References

Mary Queen of Scots by Antonia Fraser

Notes from a talk on Mary Queen of Scots Bedchamber at Holyrood Palace

Note: Rizzio is the Scots spelling of Italian pronunciation, for his name was actually spelt Riccio.