Margaret Atwood describes a good copy editor as ‘the person who will save you from yourself,’ and I have to agree. I am fortunate to have Richard Sheehan as mine. After he emerged from editing my series The Seton Chronicles I asked him if he would share some of his secrets in a guest post, which he generously agreed to do.

So here it is… from the editor’s pen.

The manuscript arrives in your email – where do you start?

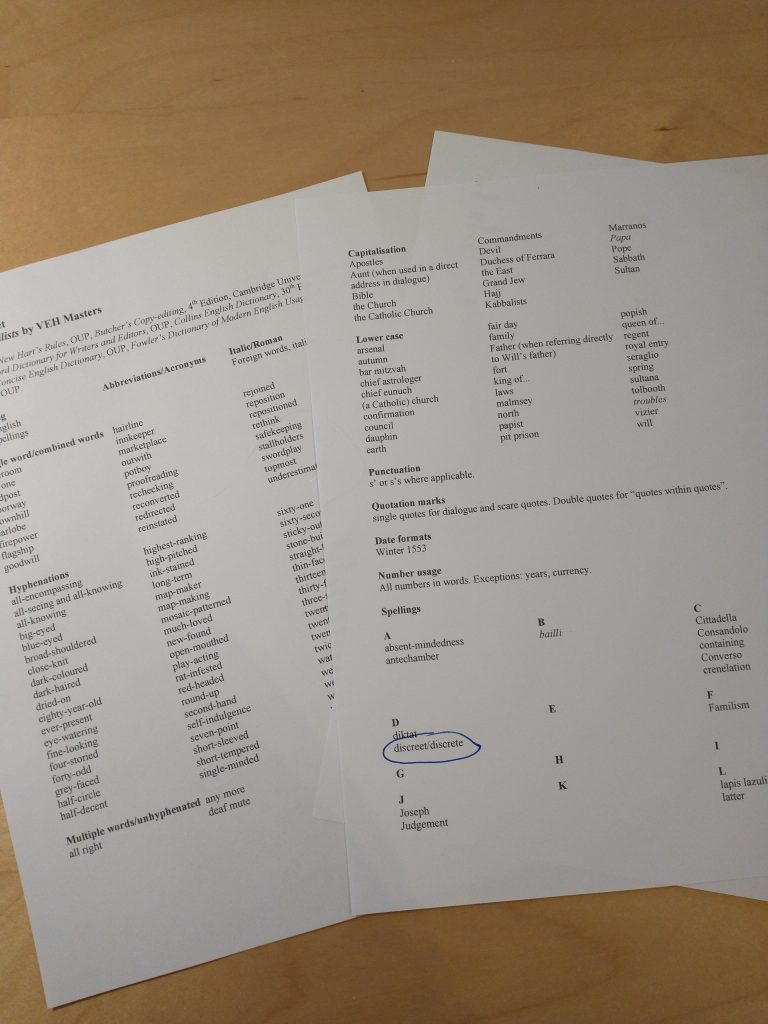

The very first thing I do I to set up a folder structure on my computer, which includes folders for the original file, the work in progress, and the completed manuscript. I then add all my standard files for my timesheet, synopsis, character list, style sheet, and editing notes.

Then I back all these up to my online storage, which I regularly back up to several times a day when I’m working on an edit.

Then I run a set of macros on the manuscript. These give me an overview of how it’s written. They show me the numbering style, the hyphenation, capitalisation, spelling errors, and so on. I work through the results of the macros and check what’s been found with the manuscript. Then I run consistency-checking software to pick up anything the macros might have missed.

Then I begin the first of two read-throughs. Every project starts this way. But from this point on, the process can differ based on what’s required.

I hadn’t realised until I started writing that there are different types of editors – can you explain a little about that and where you fit in?

There are several types of editors, and their titles vary a little depending on location, but basically there are the following:

Developmental, Content or Substantive Editors

This form of editing looks at the big picture of the manuscript. The editor will look at it overall, chapter by chapter, particularly in areas such as the structure of the novel, characterisation, plot, pace, and point of view. The purpose of this type of edit is to develop the manuscript with the writer.

Copy-editors

The copy-editor works with the manuscript in a raw form before it is typeset and will look at grammar, spelling, punctuation, capitalisation, hyphenation, use of UK or US English, consistency, style, and accuracy. Depending on the project, the copy-editor may also address some aspects of developmental editing and fact-checking.

Note: line-editing is based at the sentence level and is sometimes referred to as separate to copy-editing. However, in the UK, I’ve found that lots of copy-editors do it as part of their work.

Proofreaders

Proofreading is traditionally done after the book has been typeset and is concerned with accuracy, quality, and consistency. A proofreader will check for typographical errors, spelling, punctuation, grammar, capitalisation, hyphenation, layout, headings, pagination, front and end matter, and anything that may not have been on the manuscript that was checked by the copy-editor.

What are the most common errors you see your authors making?

Aside from the obvious typos, punctuation, and grammar issues (and I don’t mind that, it’s my job to correct it after all), these are some of the issues I come across regularly.

Dialogue Tags and Dialogue Formatting.

Tags first. Lots of writers feel that using tags like ‘said’, ‘replied’, ‘answered’, etc. is repetitive and that readers don’t like it. As a result, they begin using tags like ‘he laughed’, ‘she smiled’, ‘he cringed’, ‘she grimaced’, ‘he hurried’, and so on. These aren’t really speech tags. They don’t describe the act of speech. People don’t ‘grimace’ words. When a lot of agents and publishers see them, they think ‘new writer!’

It’s often best to stick with the more familiar dialogue tags. There has been research done that suggests that when readers see words like ‘said’ they automatically register the dialogue and ignore the repeated use of the tags. Of course, if there are lots of short bursts of dialogue with ‘he said’, ‘she said’, this can have the opposite effect. As with lots of things in writing, it’s about judgement.

I see quite a lot of dialogue formatted incorrectly. For example, something like:

‘Hi.’ She said.

It should, of course, be:

‘Hi,’ she said.

There are plenty of websites (and style guides) that will show the correct way to format dialogue.

Timeline Errors

Writing a novel is difficult, and keeping track of everything even more so. Even the most assiduous author can have problems synchronising all the action and events in their novel. Another eye on this can be vital in avoiding stinging rebukes in those reviews.

Head-hopping

This is when an author is using a multiple third-person perspective and switches regularly between points of view. The safe way to do this is to use a specific point of view per chapter or section. It’s possible to change point of view within scenes and do it well, but it’s very difficult and requires a lot of writing skill. When done badly, it appears to the reader as if they’re bouncing between characters’ thoughts and losing track of what’s happening.

I’m always amazed what you do find because I genuinely send off my MS thinking ‘it doesn’t need much’ – and it’s amazing how many things I’ve missed. Have you ever received a MS which in your view wasn’t yet ready for copy-editing? If so, how did you decide that and what did you do?

This happens more than people probably realise, and delicate diplomacy is needed.

I usually realise pretty quickly if a manuscript isn’t ready for editing. Over the years I’ve developed quite a good sense for this. It’s why I ask for samples from the beginning, middle, and the end of the text. Sometimes the first few chapters have been polished, so it’s worth seeing other sections.

Writing a book is incredibly difficult and takes a lot of dedication, persistence, and the opening up of your imagination and inner thoughts to strangers. Taking the step of looking for an editor is also a leap of faith, and, particularly for a first-time writer, an editor needs to be very sensitive to the author’s feelings. If I get a manuscript that isn’t ready for a copy-edit, I always try to accentuate the positive and suggest if a different form of editing (perhaps a critique or developmental work) might be better at this stage in the novel’s progress. Sometimes I might propose that a writer joins a writers’ group to get feedback that way. There are lots of resources to help these days; usually it’s just a case of being pointed in the right direction.

I struggle with keeping track of dates, as you know having had to pick me up a few times most recently with the MS of The Familists where I had characters older or younger than they could be according to the timeline. Have you got any tips on how I might manage this better?

There are two issues here. One is keeping track of the chronology, and the other is keeping a record of characters. When I’m editing, I keep spreadsheets for both of these.

The character list is fairly straightforward and includes fields for physical descriptions, relationships to other characters, personality traits, significant possessions, and anything else that might be relevant during the progression of the story.

The timeline/chronology can vary a little depending on the structure of the story. From short timelines and keeping track of things by the hour, to longer timelines and keeping track of days, weeks, months, years, whatever is required.

This gets more complicated if there are several timelines and sub-plots, but it’s even more important because it’s easier for threads to get out of sync. And if you’re working on a series of books, then you need to keep a check on how everything develops over the writing of them, so you probably need to keep records over a period of years.

I’ve found spreadsheets are the best tool for me to do this. The most straightforward way of doing it can be to have a row for each chapter and allocate the columns to each timeline/character. It can get quite complicated, but it’s a good way to see at a glance if there’s a problem.

How do you balance keeping the author’s voice with making sure the editing is robust?

Good question. Firstly, as the editor, you need to keep your own preferences out of it. It’s the author’s work, and whether you would write it the same way is irrelevant. So don’t change things just because you think it should be done differently.

Look for stylistic techniques that are used consistently. The use of commas is a biggie. It’s almost like a fingerprint. Look for how dialogue and thoughts are formatted. See how adjectives and adverbs are used. How are sentences structured? Lots of short concise phrasing, or long, winding digressions with multiple clauses? Or both?

I don’t think of rules in editing, I think of conventions. And it’s okay to break conventions. So if a writer breaks conventions but the story benefits, stick with it.

Most of all though, remember whose story it is and ‘do no harm’.

Any Final Thoughts?

It’s hard to think of editing as a job sometimes, because I feel so fortunate to be reading other people’s writing and getting paid for it. So it’s a great privilege, and I see my prime purpose as trying to bring the very best out of the writing I’m working on. Sometimes I just look at a piece of writing and realise that I can’t do anything, it’s wonderful as it is, but that’s okay too – don’t mess with something that’s good.

***

I started editing after a twenty-year career in IT. I’d been writing for a few years and was looking for a change of career. I spent over a year completing courses run by the Society for Editors and Proofreaders (now the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading) and The Publishing Centre, and qualified as a copy-editor and proofreader. I then started working freelance with publishers, authors and businesses, and I’ve continued doing so for the past twelve years, working on over 350 books in that time.

Richard can be contacted as follows:

Email: richard.sheehan@richardmsheehan.co.uk

Website: www.richardmsheehan.co.uk

Twitter: @RichardMSheehan

Reedsy: reedsy.com/richard-sheehan

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/RichardMSheehan/

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/richard-sheehan-b7279044/