I went to see the rock group Jethro Tull perform on several occasions when I was a lot younger. The front man, Ian Anderson, would stand on one leg playing the flute, which was fairly impressive, but what really drew the eye was the glittering codpiece he wore while doing so.

The next time I encountered a codpiece was many years later amongst the dressing up clothes at Stirling Castle. This was on a whole different level to Anderson’s which seemed remarkably discrete by comparison. Indeed, to my 21st century eyes, it was so immodestly large and protruding I was embarrassed to be caught staring at it, and moved swiftly on.

When I came to write my first novel I debated whether my characters should don them or not and wondered if they were indeed commonly worn by the men of Scotland in 1546. I decided to delve, metaphorically, into the codpiece further.

Cod, in this instance, has nothing to do with fish but was the slang for scrotum. Codpieces began as something quite practical – a small piece of cloth to fill the space between tunic and hose, serving the function of the contemporary zip fly and preserving men’s modesty. But as the fashion in doublets became shorter, greater covering was required and the codpiece became a fashion statement of itself, and a sign of virility in the early 1500s.

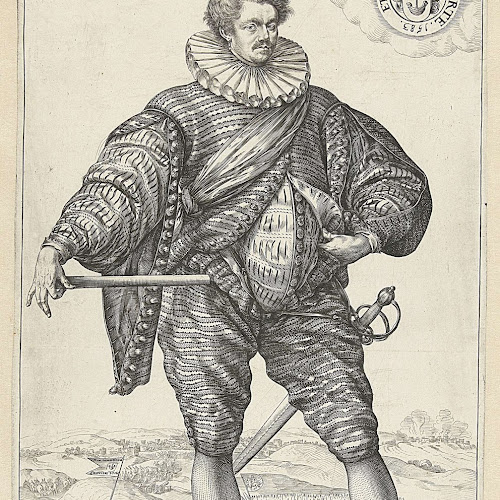

They were inevitably the provenance of the wealthy, a statement of power and masculine bravado and, as such, were worn by the swashbuckler about town as but were not acceptable wear for the humbler members of society – although smaller twill versions have been found.

Often they were decorated with tassels, bows or jewels. Some were large enough to store coins, a handkerchief or even a handy snack. The increased padding provided protection from swords, lances and other implements of war. Here’s King Henry VIII’s armour, with protective appendage

But the era of the cod piece was also the period when the pox was rife throughout Europe. Treating syphilis involved a range of herbs, sticky unguents and decoctions. Containing it all within a large codpiece helped protect clothing from stains, as well as keeping the poultice in place.

The sumptuary Act of 1562 raises ‘the monstrous and outrageous greatness’ of codpieces, although the new double ruffs worn at the neck also incurred disapproval. Both were categorised as inappropriate apparel for any but those attending court and the phrase ‘aping your betters’ was much bandied about.

In any case by late 16th century the cod piece had had its day and was replaced by the well padded stomach, known as a peascod belly; the codpiece beneath gradually shrinking in size – as in this Portrait of a Gentleman below painted circa 1580 where the codpiece only peeps out.

And did I have my male characters sport codpieces… in my third in series The Apostates one does pop up, which I had some fun with…

Bethia turned to the man on her other side who was wearing a most alarming headdress, consisting of a number of ostrich feathers set in a metal ring around his bonnet. They were dyed in alternating red and green, drawing all eyes to him and making him seem much taller than he was. Each time he turned his head the feathers brushed against the side of Bethia’s face.

‘Your plumes are most wondrous,’ she said.

He preened, proud as any cock. ‘They are come from Matthaus Schwarz, for he is the king of such designs.’

Bethia smiled politely.

‘You don’t know of Master Schwarz? I thought you were recently living in Antwerp, and he works for the Fuggers who are much in evidence in that city.’

‘I do know of the Fugger Brothers for they are great merchants but I didn’t go out much while I lived in Antwerp.’

‘You must be very happy to have left then,’ said her companion and she couldn’t stop the bubble of laughter escaping.

They discussed ostrich feathers, and the delicate task of dyeing them so they weren’t damaged, until the subject was exhausted at which point he moved onto cod pieces, standing up to display the thrust of his.

‘Look, I had my jeweller provide a few diamonds to make it sparkle and the tassels are of my particular design. It even cunningly holds this,’ he said fiddling at his package.

Bethia knew she should avert her eyes but somehow could not. She waited to see what would emerge. He tugged out a handkerchief, flourishing it to the applause of those around them.

References:

Grace Vicary, Visual Art as Social Data: The Renaissance Codpiece

Ruth Goodman, How to be a Tudor: A Dawn-to-Dusk Guide to Everyday Life

https://www.cam.ac.uk/research/features/what-goes-up-must-come-down-a-brief-history-of-the-codpiece

VEH Masters is the awrd winning author of The Seton Chronicles

Click here to buy in Australia

My monthly newsletter offers subscribers updates on research and my writing as well as a couple of free short stories (available to subscribers only) and tales of my latest castle visit.

Subscribe here – you can unsubscribe with ease at any time.