A visit to Istanbul yielded a rich seam of research for my most recent in series The Familists. Here’s some highlights.

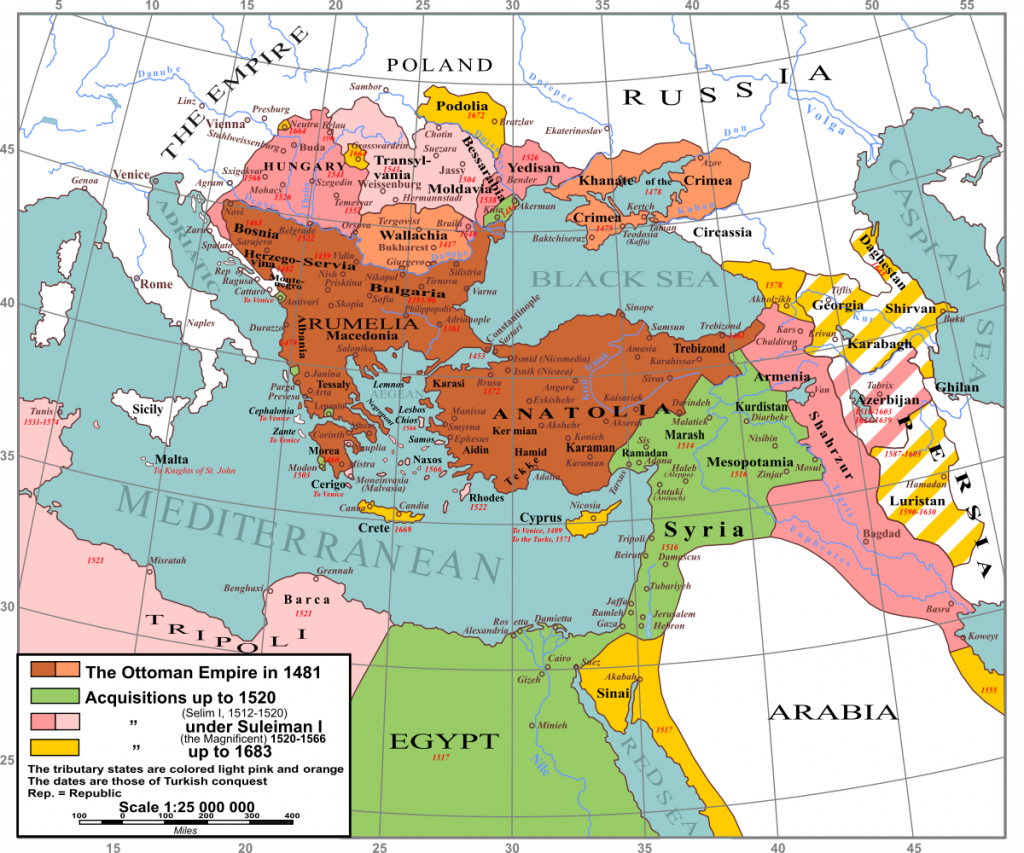

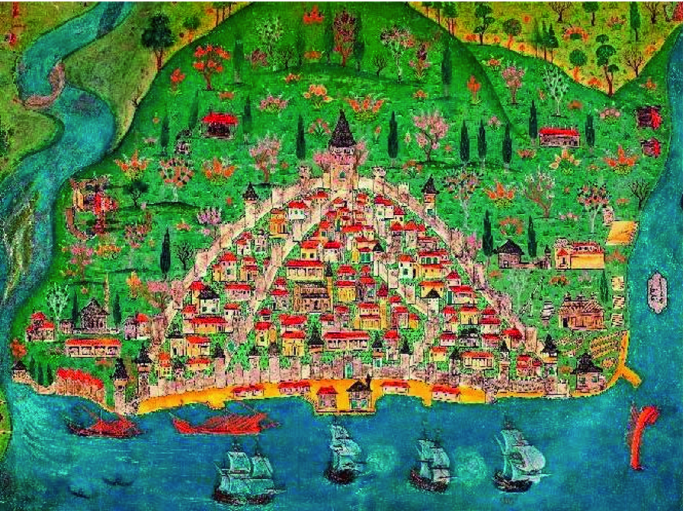

Mehmet II besieged and conquered Constantinople in 1453 and simply moved into what the Byzantines had vacated, re-purposing and repairing as he went. The stunning Hagia Sofia, built nine hundred years earlier in 537 , as the principle church of the Byzantine Empire, became a mosque

and the church within the Topkapi Palace grounds was used as an arsenal.

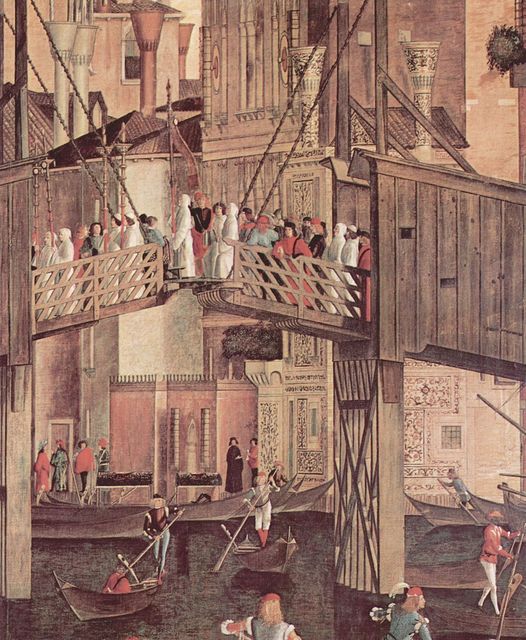

My characters find themselves in Constantinople barely a hundred years later, or more accurately, living across the Golden Horn in an area known as Galata where the many Conversos (Jews who had been forcibly converted to Christianity) fleeing across Europe finally settled .

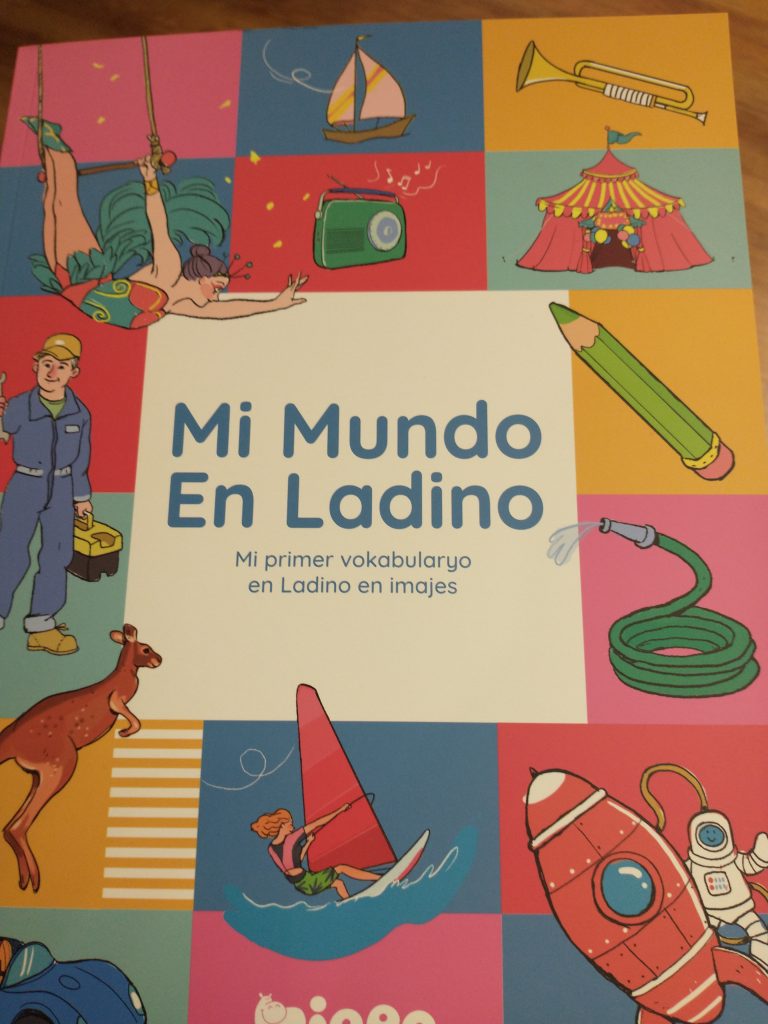

Conversos were originally expelled from Spain and spoke a Judeo Spanish known as Ladino (the Greek Jews of Constantinople who’d been there long before the Spanish Jews arrived spoke a Judeo-Greek known as Romaniote). I was very interested to see a child’s Ladino textbook in the museum of Turkish Jews in Galata

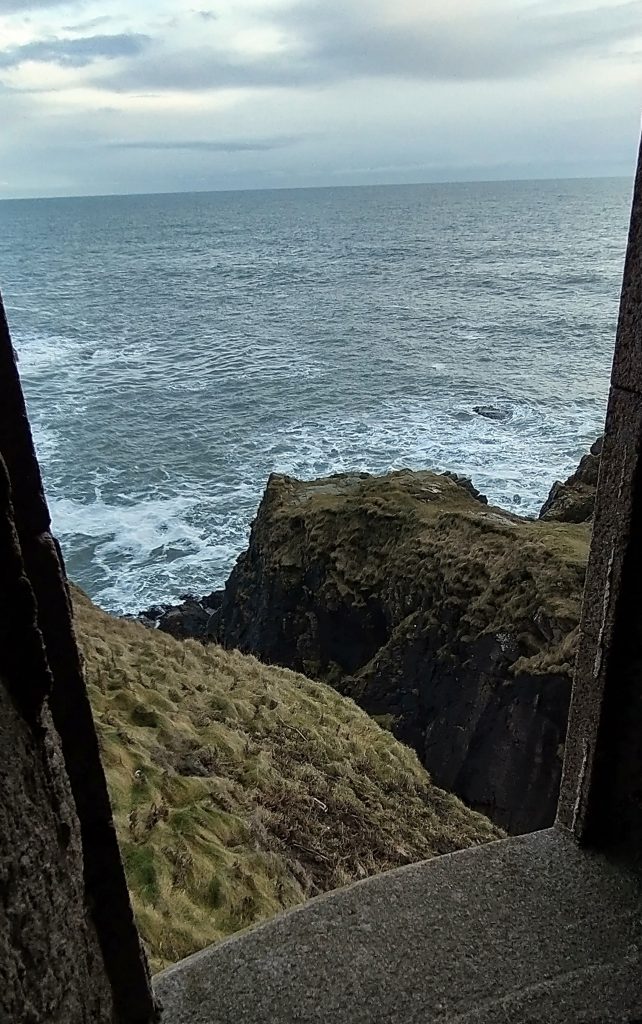

Galata is dominated still by its watch tower built by the Genoese when they captured Galata in the 1300s.

The area was famous for its fish market even then, which is well worth a visit.

I had debated whether a trip to Istanbul was necessary since I had already done a lot of research for The Familists and of course it would have changed dramatically since 1555. But I’m glad we made the trip for, apart from being a magnificent city, there were at the very least the vistas which cannot be captured in the same way through looking at images. The view Bethia would have seen whenever she crossed the Golden Horn to take goods to the harem in the Topkapi Palace or visit the Grand Bazaar would have included the Süleymaniye Mosque rising behind the city walls.

The Grand Bazaar established during the reign of Sultan Mehmed II between 1451 and 1481, is one of the largest and oldest covered markets still in existence, with about four thousand shops.

What I could never have captured from research alone was the sheer noise of the place as voices of traders haggling with customers echoed off its high arched roofs – and we were there in the evening shortly before it closed. I can’t begin to imagine how loud it must be in the middle of the day.

I am a lover of castles as those who read my newsletter will know from its regular slot covering ‘Great Castles to Visit in Scotland’ but the Topkapi Palace is beyond any castle I’ve ever visited. We were there for five hours and I barely touched the sides. Above is husband pictured at the beginning of our visit …and below after five hours. In my defence he did spend the last hour sitting reading the book on his phone.

Most fascinating of all was the tour of the harem. My character Bethia ends up running a business selling goods to the concubines who, of course, could not leave its confines. The mostly Jewish women who provided this service, were known as kiras. The harem is inevitably a more confined area than the rest of the spacious palace, with a view only of the sky from its narrow courtyards.

Even the Valide Sultan (the sultan’s mother) reception room was surprisingly small.

The eunuchs quarters are attached to the harem and also a dormitory. Indeed there were lots of dormitories within the palace for both janissaries and all the administrators who worked and lived there – around three thousand people in all during the time of Suleiman.

There were men who brought the women of the harem their food from the palace kitchens and went out onto the hillsides to chop wood for the fires – making them a strange combination of servers and loggers. These young men wore their fringes very long so their hair covered their eyes. They were never permitted in the harem proper and any young woman who found herself in the area where they left the trays of food would be in trouble, along with the server. The Chief Eunnuch held great power and controlled the finances of the harem, so the kira were paid by them.

There were lots of museums within the walls of the palace, including those displaying jewels (too long a queue to wait in), armoury, kitchen equipment as well as the courtyard where Suleiman liked to watch his menagerie of lions in action. The museum I found most fascinating was that displaying the clothes the sultans wore.

The garments were found when the palace was restored in 1924 and remarkably both Mehmet II and Suleiman’s clothes had survived for over five hundred years because of the way they’d been stored. The undershirts were especially intricate with the text from the Koran painted on in the most tiny handwriting.

It was upsetting to look at the clothes on display once worn by the sultan’s children and know that only the son who succeeded would survive after the sultan’s death – virtually the first action taken by a new sultan on succession was to order his siblings strangled.

A grim note to end upon, so I shall leave you with a picture of the amazing Turkish Delight to be found in Istanbul’s many, many confectionary shops.

Click here to buy in Australia

My monthly newsletter offers subscribers updates on research and my writing as well as a couple of free short stories (available to subscribers only) and tales of my latest castle visit.

Subscribe here – you can unsubscribe with ease at any time.