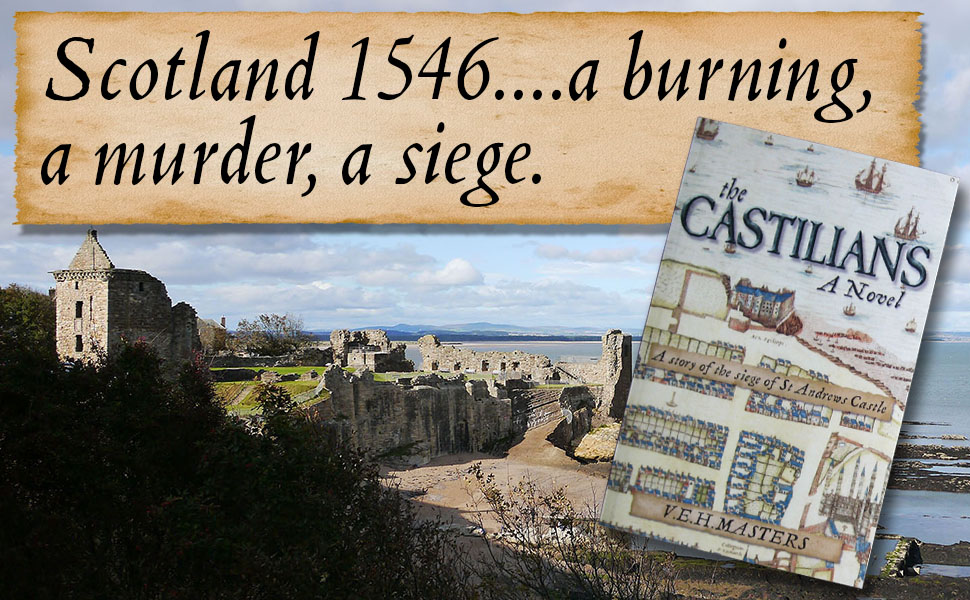

A lovely reader writes asking if I can give more detail of the locations in my books. St Andrews, where my historical fiction novel based on real events, The Castilians, is set, is my home town so I had a very clear picture of the streets my characters would walk and even the destruction wrought by the siege, and after, for much of it is still visible. For instance here’s the remains of Blackfriars Chapel, damaged by the Castilians, along with Greyfriars, in April 1547.

My old school sits behind it and I walked passed this ruin every morning without a second glance. There nothing left of Greyfriars except a street name and a row of gardens. No doubt, if the gardens were excavated, some remnants of the grey friars lives might be unearthed.

However it’s unlikely a great deal of the stones used to build Greyfriars would be left for it, along with the castle and cathedral, were systematically quarried for several hundred years, which explains why these ruins are really so very tidy, with no heaps of rubble in evidence.

The good citizens of the town used the stone to build and repair houses and to build the piers at the harbour, which were made from wood – and considerably longer – in the time of the Castilians. Below is the pier today and the hill Bethia would have toiled up when she came across the grim sight of George Wishart being burned at the stake.

St Andrews is so named because some of the bones of the apostle Saint Andrew once rested here. It was a place of pilgrimage to rival Compostela from the 1100s, with pilgrims coming from as far away as Russia. A Certificate of Pilgrimage given to a pilgrim who was undertaking the journey as part of a penance because he had murdered a man (as well as making recompense to the man’s family), was found in France a few years ago and I used this as the background for Mainard being there, although for some reason decided I wanted my character to come from Flanders and not France. A fortuitous choice since research later uncovered Antwerp was the wealthiest city in Europe at the time.

Pilgrims travelled in groups for safety. They arrived by sea, often at Earlsferry and would walk the last twenty or so miles to St Andrews. The townsfolk were understandably fearful of pilgrims bringing the plague to their doors and they were held in quarantine, outwith the city boundaries, until they were pronounced safe to enter its gates

Although the cathedral begun in 1160 and which took 120 years to finish, was surrounded by a high wall, the town itself never was. It did however have entry gates, one of which I used to pass under every day to go to school, again without paying it the slightest of attention

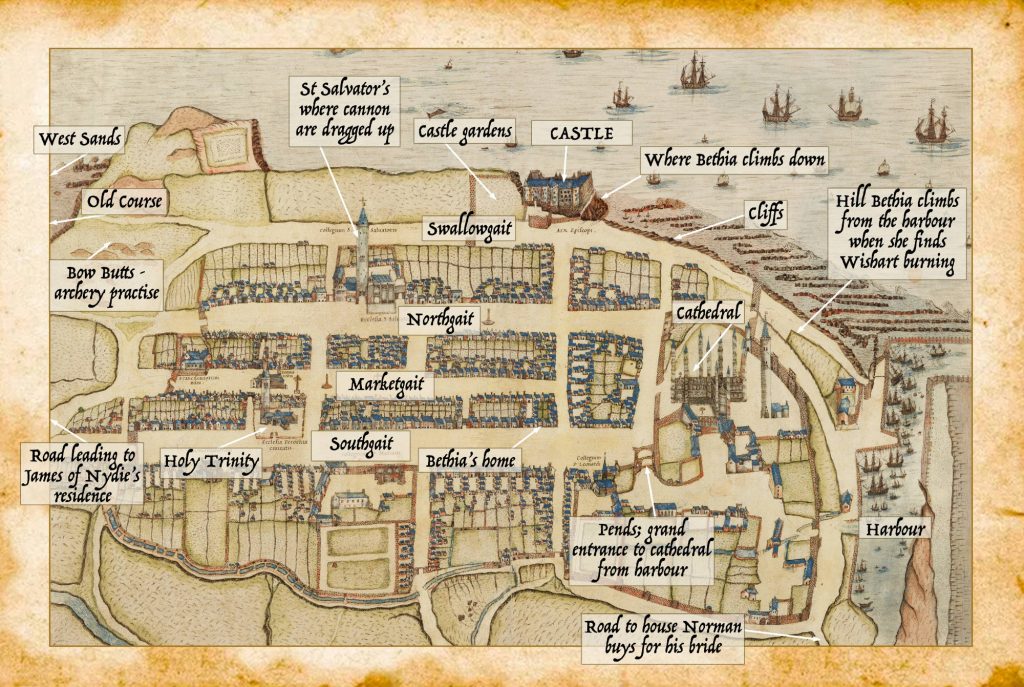

These ports or gates were all about controlling trade for the guilds; the good burghers of St Andrews wanted to make sure no one could make inroads into their living. You can see the gates on the map before which I’ve also annotated to show some of the streets and locations mentioned in The Castilians.

The town was extended and planned as the cathedral was built and the three streets fanning out from the cathedral, then known as Southgait, Mercatgait and Northgait were deliberately broad and straight for the many religious processions, including carrying the reliquary containing Saint Andrews bones along them presumably on 30th November each year (St Andrew’s day), and the performances of the mystery plays. When Mary of Guise arrived in Scotland she was met at St Andrews by her new husband, James V, and forty days of jousts, plays and street pageant followed, which must have caused huge excitement amongst the town’s inhabitants.

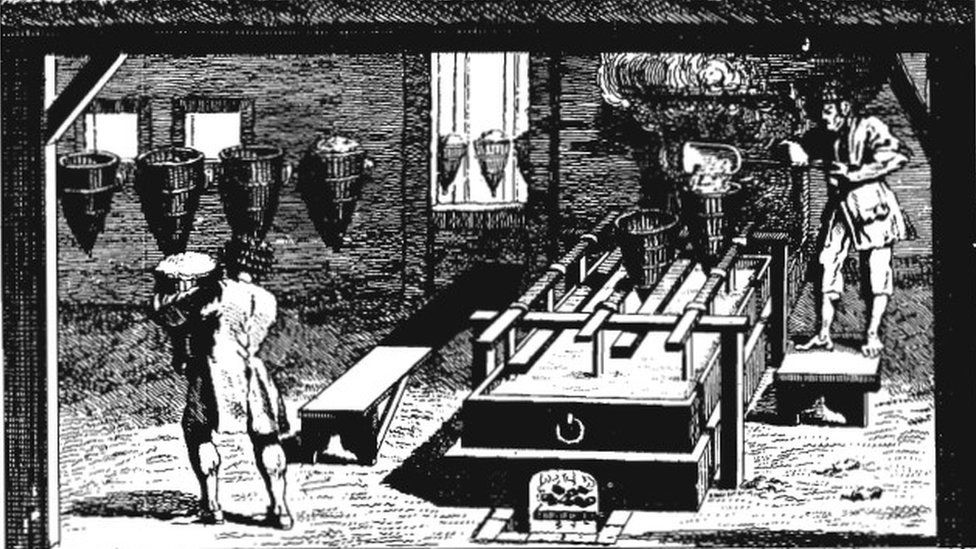

The end of Southgait closest to the cathedral was where the wealthy merchants lived and I chose a house from the era to be Bethia’s. Increasingly wooden houses were being replaced by stone although shopkeepers often had a wooden extension to the front of their house with a hatch that could be raised to create a counter to sell from – like Elspeth’s family.

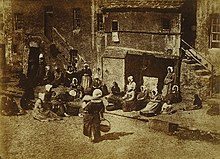

Many of the town’s poorer folk made their living from fishing. They’d been moved away from the harbour when the cathedral was built and resided in an area known as fishertoun, off Northgait. The outside stone stairs are a familiar sight in St Andrews still.

In Northgait was St Salvator’s the university chapel, where the then wooden tower atop was knocked down to create a flat base and cannon were hauled up for the bombardment which finally ended the siege. Northgait was also where the the siege tunnel was begun, and the entrance is below a house there still.

The Smart History team at St Andrews University have created some wonderful and carefully researched video models to show what the town would have looked like in the 1550s.

This video reconstruction of Holy Trinity as it may have appeared in 1559 is based on research into historical images and written records (including property documents) undertaken by Dr Bess Rhodes, Peryn Westerhof Nyman, and Chelsea Reutcke. The digital reconstruction was created by Sarah Kennedy.visual world.

St Rule’s Tower, built in 1120 is the oldest part of the cathedral complex. Climbing to the top gives a panoramic view of St Andrews, which I used to do regularly at school lunch time. Unfortunately I never savoured the view since I was scared of heights and would crawl around the top rather than look over the, then, very low parapet.

The castle ruins sits tucked away in a corner now, but once would have been as central to the town as the cathedral. To reach the harbour from the castle is a slippery walk over reefs, at low tide only, which both Bethia and Will had to undertake on separate occasions.

Here also are the cliffs Bethia had to climb down to escape from the rubble strewn castle.

The destruction of the cathedral began at the Reformation in 1560 when crowds looted and wreaked havoc. They smashed all the stained glass windows in every church, toppled any saints from their pedestals, melted down gold plate and from then on St Andrews, which had been Scotland’s ecclesiastical centre, as well as home to the country’s first university, fell into decline. Rubbish piled high in the streets and people had to climb over it to access their front doors. The town became so rundown, there was even a proposal the university be re-sited in Perth.

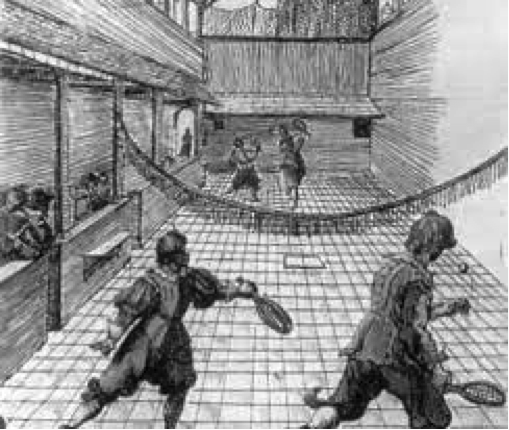

Eventually St Andrews was re-purposed as the home of golf as well as an ancient university town. Golf was actually banned by James II in 1457 because he felt young men were playing it rather than practising their archery. The Bow Butts, a lane named for the place of archery practice, is found near the West Sands and at the side of the first tee of the Old Course.

James IV however was a keen golfer and re-instated the game fifty years later.

If you haven’t already read The Castilians it gives much more of the story of the town and the siege of 1546.

It can be bought from:

Amazon US here

Amazon UK here