Culross is a very pretty village set on the opposite of the Firth of Forth to Edinburgh and one of the locations used to film the Outlander series. Sitting in a café there I got chatting to a lovely American who was on an Outlander tour.

‘We did Edinburgh yesterday,’ she said, ‘and we’re doing the Highlands today.’

‘Wow that’s a long way in a day,’ I said.

After a rather confusing chat, I suspect for us both, I realised it was the locations used to film Outlander’s Highland scenes, rather than the actual Highlands the tour group was visiting. Having clarified we were in the Scottish Lowlands, we went on to have a good blether and agreed that Scotland was not overfull of men as bonny as Jamie.

The encounter left me thinking about perceptions of a country that are formed by reading historical fiction. There’s no question that Diana Gabaldon’s Outlander series has given Scotland’s tourist industry a huge boost and all credit to her that she wanted Scottish locations used for much of the filming, however she’s not the only historical fiction writer to have had a massive impact on visitor numbers to Scotland.

I first became aware of Sir Walter Scott as a child on a rare and exciting visit to Edinburgh, when the iconic monument built by public subscription in his memory was pointed out. The tiers of sooty spikes and great height left me, even aged ten, impressed. Who was this Scotsman so famous that he had a most elaborate edifice erected in his memory (and, amongst many other accolades, Edinburgh’s Waverley Station named after his novels) and yet I’d never heard of him?

I’d like to say I was curious enough to find out more, but I forgot all about the man, and his monument, until some years later when, as the reader in the family, I was given the complete set of Sir Walter Scott novels which had belonged to my great grandfather.

My hunger for books was vast, and mostly unrequited in those days. I started with Ivanhoe, which sounded romantic. I’d never read anything like it – dense, rich, complex, difficult – and medieval, an era I’d little knowledge of. But also frustrating…why did Ivanhoe ride off into the sunset with the vapid Rowena when Rebecca, a woman of power and strength, had saved his life. What did it matter that they were of different religions? I didn’t believe Ivanhoe loved Rowena. All credit to Scott though, for Rebecca was the first positive Jewish character I’d encountered in literature and a refreshing counterbalance to Shylock and Fagin.

Sir Walter Scott is known as the founder of the historical novel, in English literature. And not only did he create a great, and fictitious, romance about Scotland through books such as Rob Roy and his long poem The Lady of the Lake, he also influenced how Scotland appeared to the world. It has been said he ‘invented’ Scotland. Soon travellers flocked here and indeed he did for our fledging tourist industry in the nineteenth century what Diana Gabaldon has done in the twenty first century.

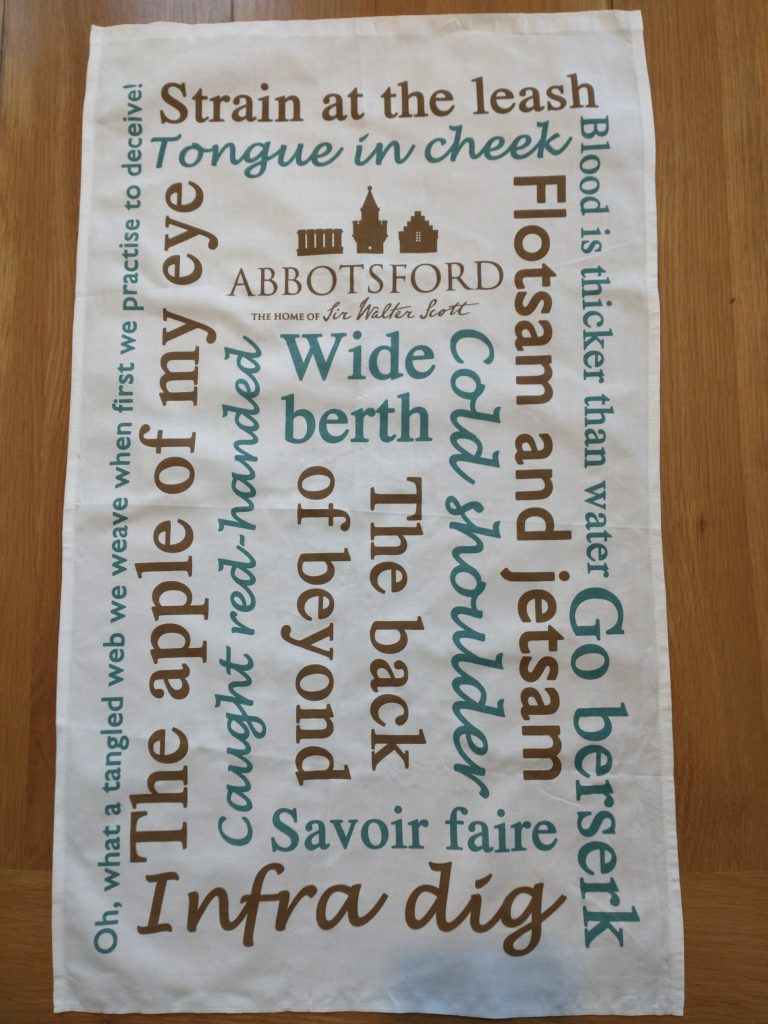

Scott’s also responsible for a surprising number of expressions we use – see the tea towel pictured above purchased from his home at Abbotsford (which is fantastic place to stay – for more on this and Scott see my blog post https://vehmasters.com/why-is-it-called-a-thunderbox).

But Scott lived in the Scottish Borders and Edinburgh, not the Highlands. The Highlands has its own distinctive culture and Highlanders were often referred to as teuchters by Lowland Scots which, like sassenach, is a term of derision and contempt. Influenced by Scott, paintings of the Highlands were in demand, with the work of Landseer particularly popular. Yet it is sadly ironic that during the era Landseer and others were painting a stylized version of the Highlands, large numbers of local people were being brutally forced off the land to make way for sheep.

Queen Victoria read and loved Scott’s books and much ‘redesigning’ of historical buildings took place during her era, often influenced by his work. Here’s the Great Hall at Edinburgh Castle. Its hammerbeam roof, completed in 1511 during the reign of James IV, is the only part which was not altered by the Victorians to fit with their vision of history.

And what of the impact such romanticisation can have on a country and its heritage? The film Brigadoon, made in the 1950s, is about two American tourists coming upon an enchanted village while lost in the Highlands. The producer toured Scotland searching for suitable locations. Rejecting them all he returned home saying, ‘I went to Scotland but could find nothing that looked like Scotland.’ Instead he created his own vision of Brigadoon in a Hollywood set.

Visiting our son and his family in Kobe, Japan last year I passed a vending machine every day which had been painted in the colours of Kobe Tartan. Scotland is famous for its tartans and yet their clan associations are a made up part of our heritage. The wearing of ‘Highland garb’ was banned after Culloden, although the Proscription Act was repealed barely thirty years later in 1782. By the time George IV came on his state visit to Edinburgh, orchestrated by Sir Walter Scott in 1822, tartan was fashionable enough for the king to appear in full Highland dress – but a much richer and more stylised version than anything that would ever have been worn in the Highlands.

Tartan as we know it is a construct of the early nineteenth century led by an opportunistic Bannockburn merchant called William Wilson who created a list of tartans by ascribing clan names arbitrarily to them. When Queen Victoria bought Balmoral Castle and be-decked it with tartan, then what the book ‘Scotland the Brand’ refers to as the Tartan Monster was born.

A wee whilie ago, I came across a guide who gives knitting tours of Scotland (love that!) She also does more standard tours which include St Andrews, the location of my first in series. The Castilians is about the siege of St Andrews Castle in 1546 and the inciting incident was the burning of a protestant preacher.

‘I tell my tourists that story,’ the guide said, ‘and of how Cardinal Beaton stood at the tall window of the castle watching George Wishart burn with a glass of wine in his hand, his mistress by his side, smiling.’

I winced and explained there was no evidence Beaton’s mistress was there. I went on to explain that some historians believed the cardinal thought it was his duty to watch to the end and, from the research I did it appears he ordered plenty of gun powder hung around Wishart’s neck so his suffering wasn’t too prolonged.

I could see she was disappointed and suspect she may stick to her more dramatic version of this tragic event. Tour guides are there to entertain, as much as to inform, and as with writers of historical fiction, there is a balance to choose between accuracy and engagement. Walking up the Royal Mile recently I overheard a guide giving his spiel – ‘hangings in Edinburgh were attended by huge crowds,’ he said loudly so the large group clustered around him could hear. ‘And, as part of the party atmosphere, lots of alcohol was drunk which is where,’ he paused for dramatic effect, ‘the expression hung over comes from.’ His audience laughed in appreciation. Made curious I looked up hung over and, although there’s some debate as to where the expression originates, there’s no mention of it having anything to do with the after effects of over imbibing while watching a hanging.

So, if heritage, certainly in Scotland, has become a construct to bolster the tourist industry, then what about its history and the responsibility, of writers of historical fiction, to the countries we write about?

With my first book, The Castilians, I was exploring a significant event in my home town, which is also home to Scotland’s oldest university, and I felt under pressure to get the facts right. I was curious as to the broader ramifications of the siege, having only been told it from a post reformation and thus protestant perspective. Were the protestant lairds who killed the catholic cardinal really the good guys? They were not.

I believe that as a writer of historical fiction I have a responsibility to do my research thoroughly, whilst accepting I can only write from a 21st century understanding in terms of the history I retell and remembering it is about entertaining my readers too – else I’d have none. And yet, the entertainment factor is also responsible for the explosion in historical fiction set in Scotland seeking to capitalise on the Outlander phenomenon, much of which is both poorly written and researched.

Nevertheless is it really such a bad thing to romanticise a nation? Scotland, as with any other country, is an amalgam of what happened in its past and if some of that was fabricated then that too becomes part of who we are. In endeavouring to write fiction based on sound research then we can go some way to mitigating the effects of fabrication. And if tour guides want to tell a few embellished tales so be it because, frankly, it’s fantastic people want to visit our beautiful country.

References: Scotland the Brand by David McCrone, Angela Morris and Richard Keilly, Edinburgh University Press