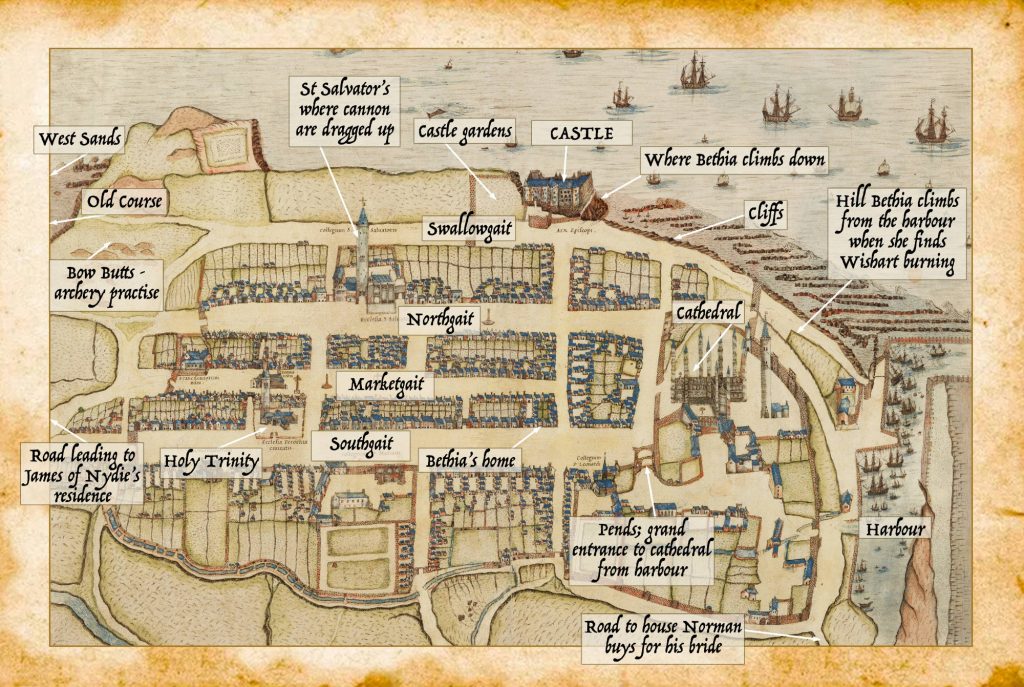

If you’ve ever been to St Andrews you’ll know it’s not only the home of golf and site of Scotland’s oldest university but the town itself is steeped in history. Once a great centre of pilgrimage, the cathedral was left in ruins after the Scottish Reformation in 1560. Although I grew up in St Andrews the ruins were simply part of the backdrop of daily life. I was twelve years old before our history teacher, Miss Grubb, took us to visit what was left of the cathedral.

We also visited the castle where there is there is the most remarkable siege tunnel, dug in 1546 and the best surviving example of siege tunnelling in Europe from the era.

You enter it from the side of the dry moat via a steep and uneven few steps. Almost immediately you’re bent double and for anyone who is at all claustrophobic a quick retreat is in order.

Creeping down the central trench, at constant risk of scraping your back on the rough stone above, you come to a fork which leads to a dead end. You retreat and continue along the main tunnel, the sense of being squeezed growing ever greater until you can barely draw breath. Then suddenly the narrow passage ends. There’s a wall of rock before you and nowhere to go. Yet looking down you spy a narrow entrance.

Dare you squash yourself throughand descend the metal ladder to find out what’s below? Down you tentatively go and the space opens out.

The tunnel is a tale of two halves and this part is broad and high with steps leading to the sealed off entrance beneath a house in North Street. There’s also a grating visible, which my brother and his friends entertained themselves during school lunchbreaks by howling down from the street above, to terrify (or perhaps create atmosphere for) the tourists beneath.

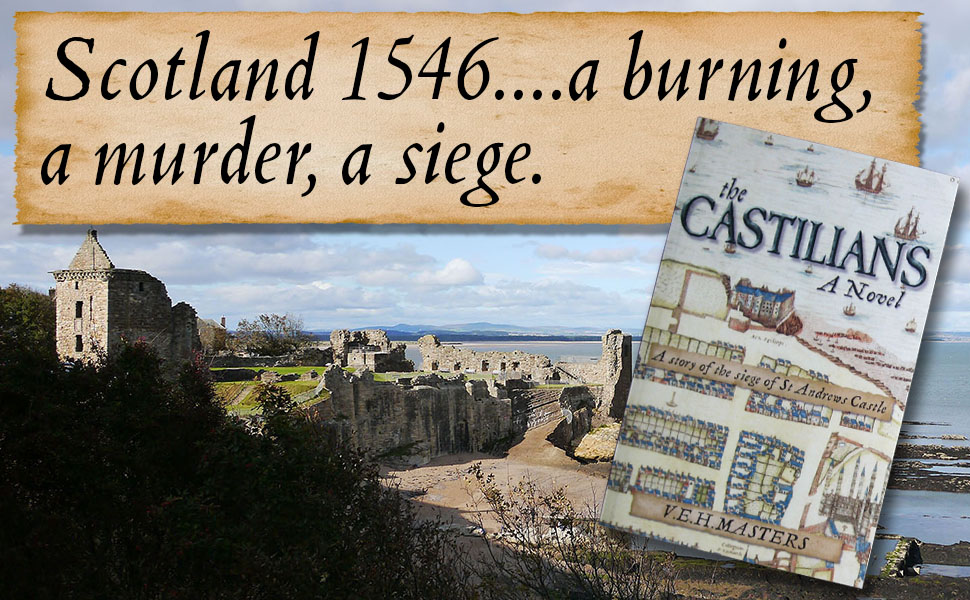

From the moment I first went down the siege tunnel at St Andrews Castle I was utterly entranced. And when I learned the men who had taken the castle early one morning by stealth, murdered its cardinal in revenge for the burning of a Protestant preacher, and held it against all comers for the next fourteen months called themselves ‘the castilians’ I felt a shiver of foreknowledge. What a perfect title for a book, I thought… I didn’t know then how very long it would take me to write it!

I did however always wonder what the point of tunnelling in was. Surely as soon as the besiegers popped their head up out of the tunnel it would likely be knocked off? When I came to do the research for The Castilians I finally understood.

The information is in the name – I have so far referred to this long underground passage as a siege tunnel and was confused as a schoolgirl why it was called the mine and counter mine.

It was never the intention of Mary Queen of Scots forces (we are in the period of regency and Mary is only 3 years old) to tunnel into the castle, capture the Protestants holding it and thus break the siege. The purpose of digging was to undermine the curtain wall, set explosives beneath it, bring it down and then storm the castle.

This is why, when you go down the tunnel/mine it’s a tale of two halves. The first part is low and narrow and clearly dug at great speed. Once you climb down the iron ladder into the second part it’s wide and high.

The besiegers began to dig in what was then known as Northgait, now North Street, at the back of a house, and hidden from those patrolling the castle walls. The aim was to dig secretly and deep until they gauged they were beneath the curtain wall. They’d then support the roof of the mine with wooden props, set explosives around the props, light fires and run fast as they could out the tunnel before it blew. The explosion would bring down part of the wall, the troops would charge and the castle would be re-taken.

But…this is the great era of siege warfare and those who are holding the castle are well aware their besiegers will likely try to get them out by undermining the walls. One of the ways those inside the castle could ascertain if mining was happening was to set up bowls of water around the courtyard and see if the water was rippling – a sign of underground activity.

In the case of the siege of St Andrews Castle those within were fairly certain the besiegers were tunnelling in. The aim then was to counter mine out as fast as they could and intercept the mine before the besiegers got beneath the curtain wall.

The challenge was to work out where the besiegers were actually digging if they were to intercept them and inside the castle there are a couple of very deep holes to be found – false starts. Eventually they found the right spot… here’s an exert from The Castilians

They hear sounds of alarm; it seems they are discovered. Any attempt to stay quiet is given up and they excavate as hard and fast as they can. Someone has fetched Richard Lee and he pushes past Will, directing them to attack the ground beneath, and not before them.

‘We must be quick,’ he hisses, ‘else they’ll have time to set explosives and blow us into eternity.’

Will shovels the rubble behind him to keep the area clear for the miners to work – there’s no time to scuttle back up the passageway with it now. A hole has appeared in the floor of the tunnel. Lee has a man shield the candles, whispering that he needs it dark to see if there’s torchlight shining through from below.

Will, Lee and the two miners huddled together in the cramped space nudge one another, there is a light. They enlarge the hole, cries from below growing loud, then fading. Lee kneels at the edge, and sticks his head through. Will can feel Lee’s body tense, ready to pull his head back. He is a brave man. They wait.

Lee lifts his head out and smiles. ‘It could not be more perfect.’

I still wonder at the amazing feat to dig, and dig so fast. There’s little reference to it in the papers of the time. The French ambassador to the English Court mentions the mine and counter-mine in his letters of November 1546, but by December it’s over and the attempt to break the siege has failed again…

If you’re ever in St Andrews Castle, don’t forget to go down the mine and counter-mine. The entrance is not obvious to find, sited as it in the side of the dry moat. It’s one of the most atmospheric places you’ll ever visit.

And in answer to the question, how do you dig a siege tunnel…by cunning, subterfuge, courage, determination and punishingly hard work.

The Castilians, the first in series of The Seton Chronicles is available as an ebook, print and audio book.

To purchase in UK click here

To purchase in USA click here

To purchase in Canada click here

To purchase in Australia click here