In my most recent book, The Apostates , my characters Bethia, Will and Mainard are forced to flee across Europe. I was curious to uncover their likely means of travel and just how perilous the journey would be.

Researching I came across a delightful book called Touring in the 1600s, and was surprised to discover that, even then, people chose to travel rather than have it forced upon them. Although the era of pilgrimage had faded – St Andrews in Scotland once a huge centre for pilgrims had seen a decline well before the Reformation – artists and a sterling few curiosity seekers did travel for pleasure, mostly to Italy.

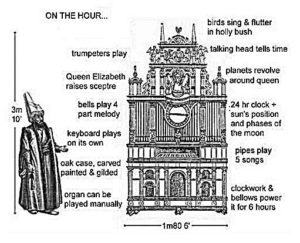

But still virtually all journeys were taken out of necessity, either for business or on the orders of others. Thomas Dallam, for instance, was a master organ builder who Elizabeth I sent off to Constantinople with her gift of an organ to Mehmed III. Dallam was then required to play the instrument for the sultan which he did with great trepidation having been forewarned that to lay a finger on The Grand Turk meant instant death – and the sultan sat so close behind Dallam to watch that ‘I touched his knee with my breeches’.

Any journey, whether embarked upon willingly or not, was difficult, dirty and uncomfortable. Roads were likely to have great potholes, often dug by the local villagers for materials to repair their homes. Travellers were advised to never journey without food in their pocket, if only to throw to the dogs who attacked them, and to line their doublet with taffeta since it was lice proof.

Another excellent piece of advice was, ‘when going by coach, to avoid women, especially old women for they always want the best places.’ Although generally if you were a woman, or married, the recommendation was to avoid travelling.

By water was the fastest means of travel, and the rivers and lakes of Europe were well supplied with boats. They were towed, or sailed, between towns with fares fixed by the local authorities, although there were complaints about drunken boatmen, who frequently landed their passengers in the water.

An account by an Italian priest en route to Amsterdam, tells how he and his fellow passengers travelled by night in an open barge unable to sit up, much less stand, because they were at risk of a severe dunt on the head from the low bridges which were invisible to the eye in the moonless night. He adds that they were forced to lie in the pouring rain, on foul straw as if they were “gentlemen from Reggio,” – a synonym for pigs.

Travelling across lakes could be perilous too, because of storms, as this account reveals…

‘The boat was made of fir-trunks, neither sound, nor tarred, nor nailed. A storm came and the helmsman left his post and called out to all to save themselves, if they could; nothing was to be seen but rain and lake and perpendicular rock until a cave was sighted towards which all joined in an effort to row. We found a way up the rock and , at the top, an inn.’

Yet finding an inn didn’t mean a traveller was in a place of safety. Inn keepers were often in cahoots with thieves, letting them know when those with an abundance of goods were in residence. Travellers were warned to check their chamber carefully and to look behind any large painting in particular, in case it concealed a secret door or window through which a robber might enter in the dark of night.

And as for Bethia, Will and Mainard’s journeys, they do have a tumultuous time… read The Apostates to find out more.

References:

Dallam’s Voyage to Turkey, The Musical Times 1905

The Sultan’s organ: presents and self-presentation in Thomas Dallam’s “Diary”: article by Lawrence Danson

Touring in the 1600s by E S Bates