Visiting Venice last year I had the opportunity to delve into aspects of city life in the 1550s, all helpful research for the then work in progress, The Apostates. For instance, the current Rialto bridge wasn’t in existence when my characters were living there, in fact there was no bridge at all at the time since it had collapsed under the weight of a crowd rushing to watch a wedding.

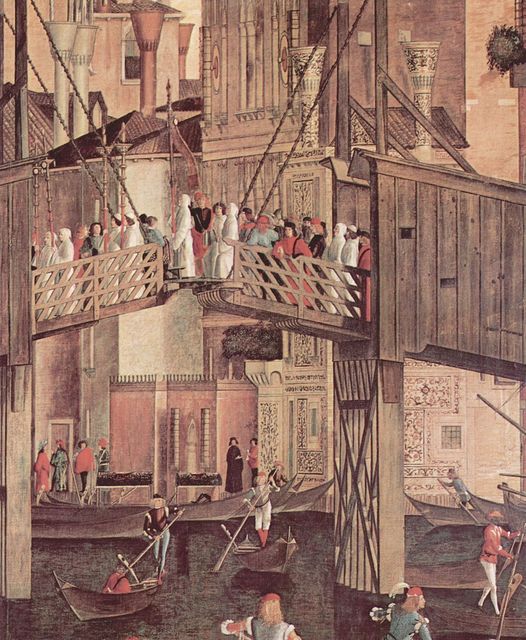

The city fathers were determined to replace previous wooden bridges with a stone built one that would last (see the painting below by Carpaccio of an earlier bridge made of wood) and asked Michelangelo, amongst others, to submit a design. When the Rialto Bridge was finally erected, many assumed it too would collapse from the weight of the marble, especially since it had no central supporting pillar. The gondoliers no doubt were very happy that it took thirty odd years before the new bridge was constructed since they provided the only means of crossing the Grand Canal.

In writing The Apostates it would’ve been all too easy to assume the current Rialto Bridge, finished in 1591, would’ve been in existence. It’s those small details which can really catch a writer of historical fiction out – or this one anyway.

My research is never particularly well planned, more a stumbling on curious facts and following my curiosity. For example, cities in Europe during the era were invariably bounded by high city walls, very necessary for their defence, and yet Venice has no such defences, apart from the Fort of San’Andrea. However the canals themselves formed a line of defence. There were markers in the very shallow water within the lagoon to guide ships and boats, which could, at need, be removed making any attacker likely to run aground.

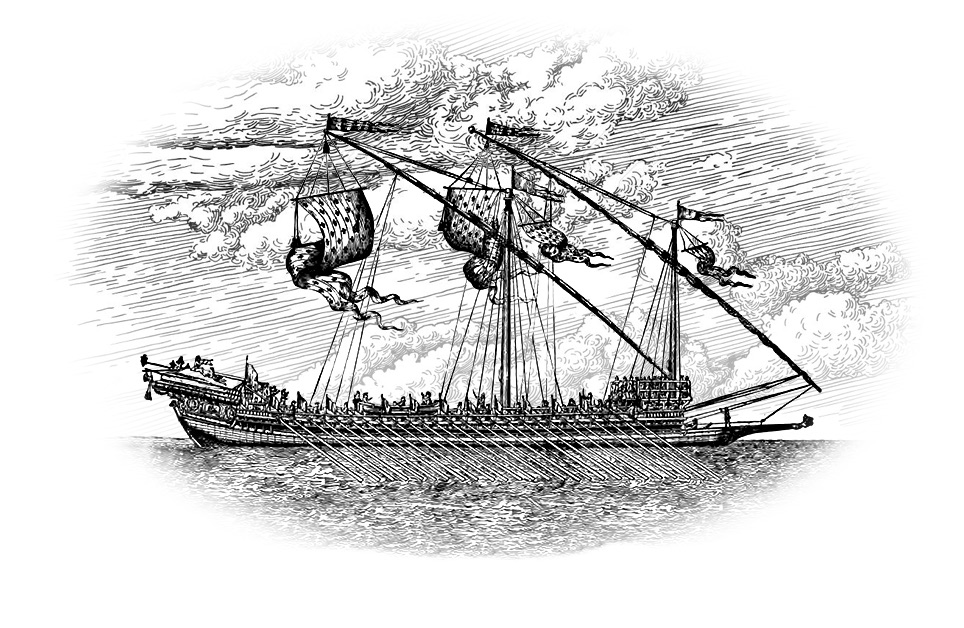

Nevertheless I found it curious that the Ottomans had never attacked – if they could take Constantinople then Venice wouldn’t have posed much of a problem. Although at times they were at loggerheads, the two regimes kept ambassadors permanently in one another courts. Cyprus for instance, was under Venetian rule and in 1570 Famagusta was besieged by the Turks yet it never erupted into open warfare between the two states. The Venetians eventually surrendered Famagusta in 1571 but the Turkish commander, furious that he’d lost over 50,000 men, breached the terms of the surrender and murdered all the Christians left in the city then flayed alive the Venetian commander.

In response the Venetians, in an unusual alliance with Spain and the Pope, won the sea battle of Lepanto and displayed the heads of the Ottoman commanders on their ships (which I cover in the most recent in series, The Familists). But these territorial skirmishes never resulted in an open declaration of war between the Doge and the Sultan. The smooth flow of trade, it seems, was more important than territory.

The islands of Venice sit within a tidal lagoon and the waters rise and fall by several feet each day. Even in the 1400s there was a concern about how to maintain the depth of the canals, which were the receptacles for all the sewage, detritus and general rubbish of the day. Leonardo’s design for a dredger was never actually built but it shows the pre-occupation with depth.

We booked a tour of the secret rooms and hidden passageways of the Doge’s Palace. Here’s the torture chamber where a prisoner could watch, from the small square window high on the right, his fellow inmate being tortured knowing it would be his turn next.

The cells in the basement of the Doge’s Palace flooded when the tide came in so prisoners would find themselves waist deep in water every twelve hours. The wealthier prisoners were held in the attics, which had the benefit of being dry but they either baked in the summer or froze in the winter beneath the lead roof.

The two pillars in St Mark’s Square, one with a winged lion and the other with the figure of St Theodore patron saint of Venice atop, were a gift from the Byzantine Emperor in the 12th century. Brought from Constantinople, there was a third column but it fell off the ship into the sea. In the era in which my books are set any member of the aristocracy sentenced to death would be hung between the two pillars and his body left swinging there for several days as a warning to others.

Visiting Venice was incredibly helpful to get a sense of the sheer scale of the buildings and the opulence my character Bethia, a wee lassie from St Andrews in Scotland, would have been exposed to. In the first in series The Castilians, Bethia’s mother is obsessed with having a painted ceiling but it would’ve been much diminished next to the grandeur of Venetian painted ceilings such as the one pictured above.

The Scuola Grande was an organisation of merchants and others who did charitable works – a precursor of the Rotary Club perhaps – but they clearly needed a grand setting in which to meet and chat about those good works.

The mosaic marble floors too would have been stunning, and so smooth underfoot for a Scottish lass.

Venice is a city of light and water and flowers. But windows then still had opaque glass. Here’s one from Ferrara that has survived for five hundred years – not great for letting in the light but very beautiful to look upon.

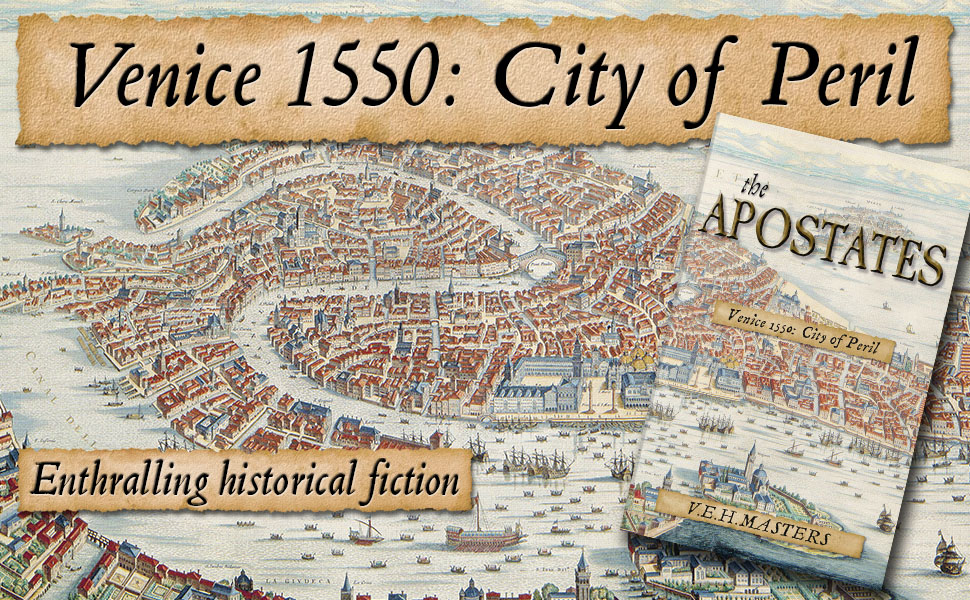

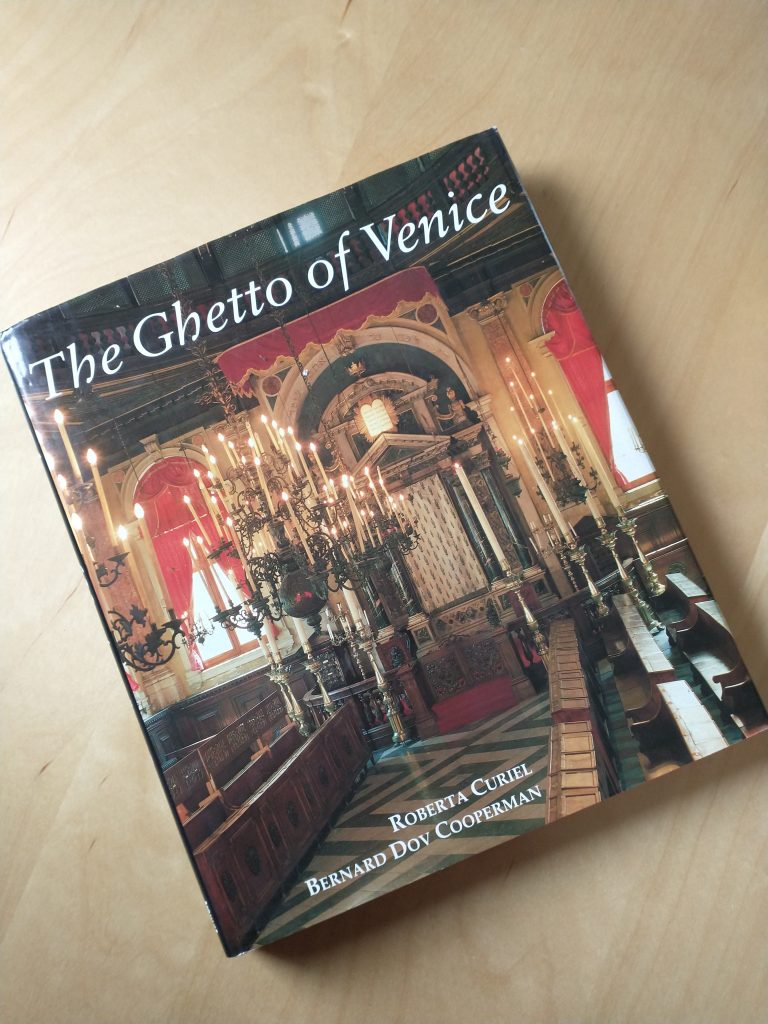

My third in series, The Apostates, is set partly in Venice.