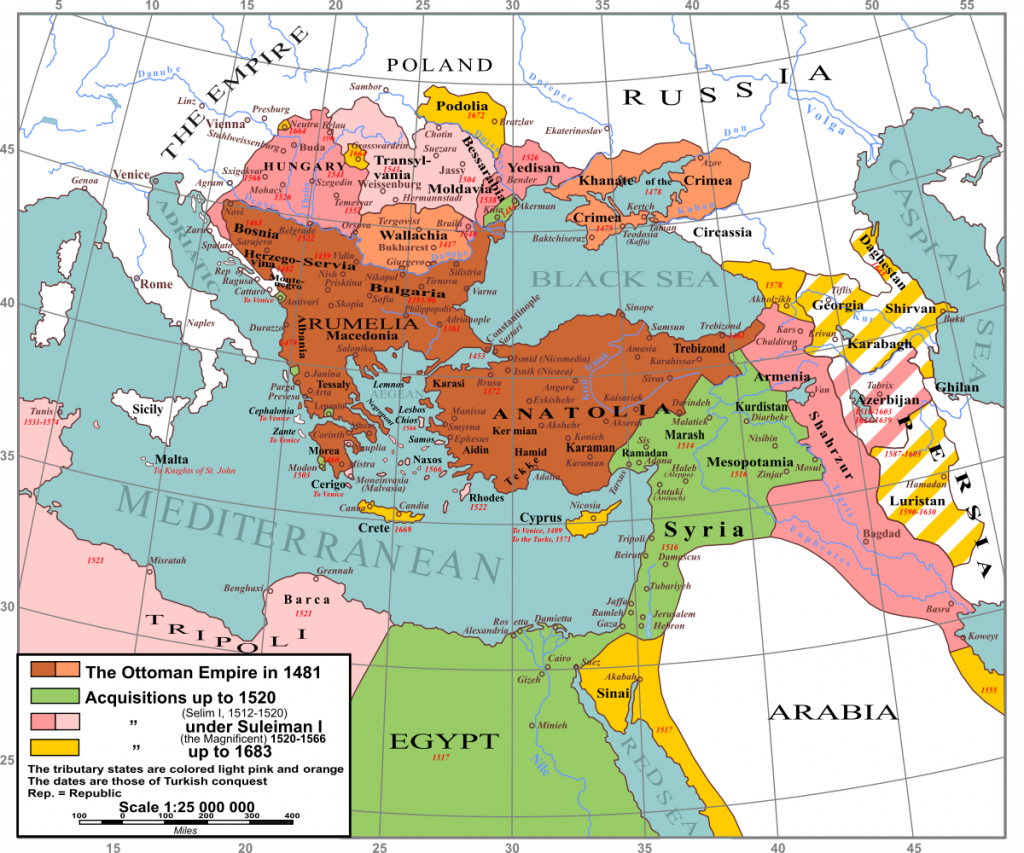

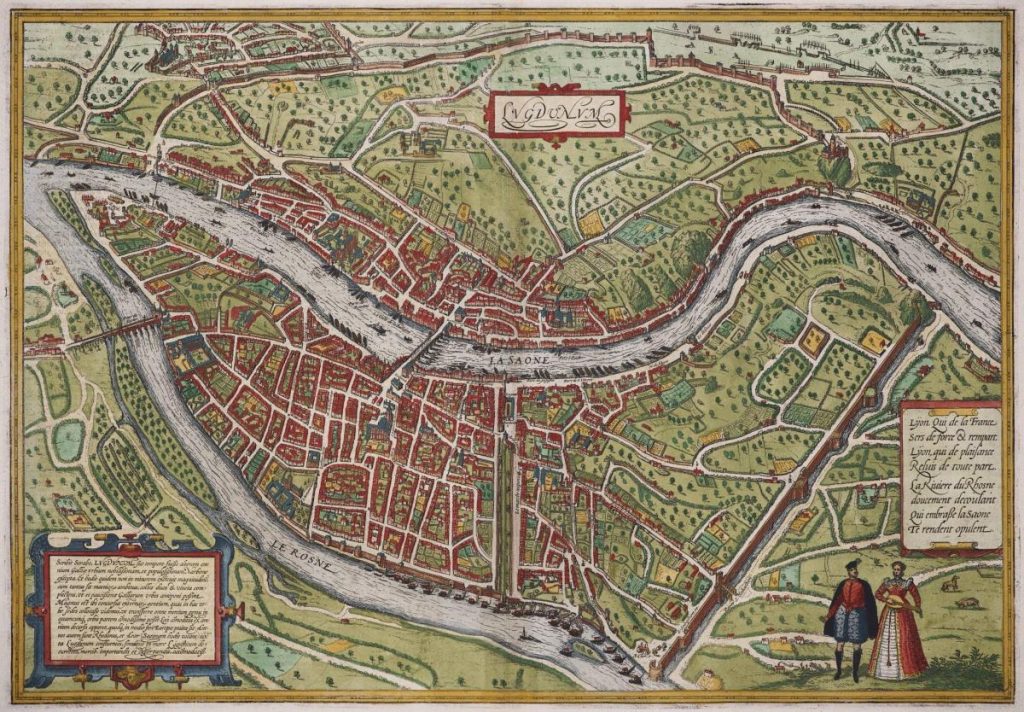

A coronation is one way of royals putting on great pageant to keep their subjects entertained and conscious of their king or queen’s magnificence, as we are fully aware of in the UK currently. Yet during their reign monarchs needed to remind their subjects periodically of the king’s overarching importance and power. In the 1500s, the period in which my books are set, the kings of France and Charles of Hapsburg regularly went on royal tours, officially known as ‘A Joyous Entry’.

These were pageants beyond what we could even begin to imagine where towns endeavoured to host the most remarkable royal entry the king had ever experienced and also subtly sent reminders to their monarch of why the town’s burghers, merchants and dignitaries needed to be kept onside.

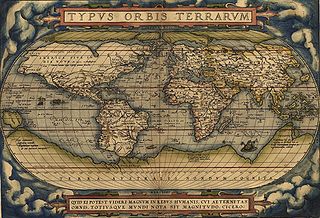

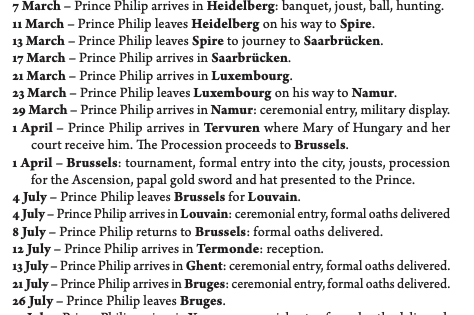

In 1549 the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles of Hapsburg went on tour with his son Philip of Spain. This extract below from their itinerary shows just how busy the programme was. They spent 20 months travelling across their territories in Italy, the Low Countries and Germany.

Philip was born in Castile and knew little about the lands he was to inherit, nor any of their languages, so the good burghers were at pains to ingratiate themselves, with each town determined to outdo their neighbour.

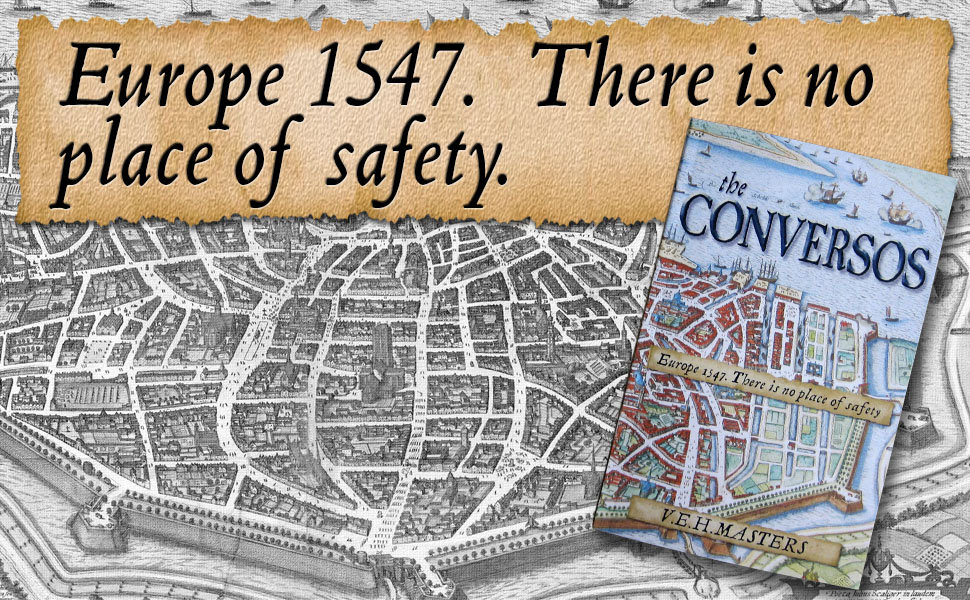

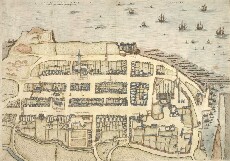

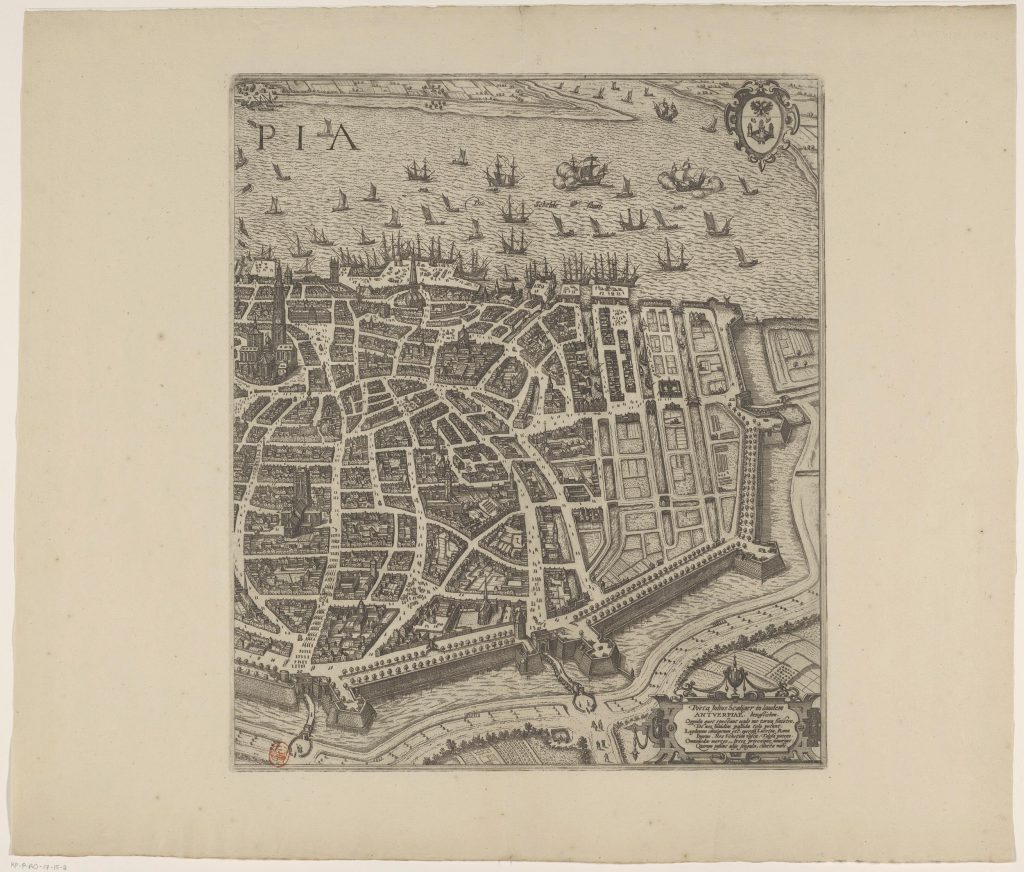

They reached Antwerp in September 1549 and I used their Joyous Entry to that city as a plot point in my second in series The Conversos . It was a rich seam to research the preparations and symbolism for the royal visit, with some wonderful titbits of detail. For instance the merchants of Florence got into a fight with the Genoese over which group should get precedence in the parade as Papa tells…

‘The Genoese claim they had precedence in both Granada in 1526 and then at Charles’s coronation in Bologna in 1530. The Florentines counterclaim that Florence was not present at either Granada nor Bologna and therefore the Genoese claims are an irrelevance – and refer to events nigh on a quarter of a century ago. The world has changed much since then.’

And how was it to be resolved?

‘We have reached an impasse. All that can be done is for the two delegations to lay their case before the emperor and let him decide. My advice to both would be not to do such a thing. It will only incur his displeasure, and this is a time to seek favour.’

Wise advice from Papa which unfortunately wasn’t followed for, when presented with the case, Charles of Hapsburg, who was nobody’s fool, declined to make the decision and ordered both parties to withdraw from the event. It’s interesting to note there are rumours at the moment of our current king in the UK having to resolve disputes – almost inevitable, I suppose.

Here’s a little more from The Conversos on the preparations…

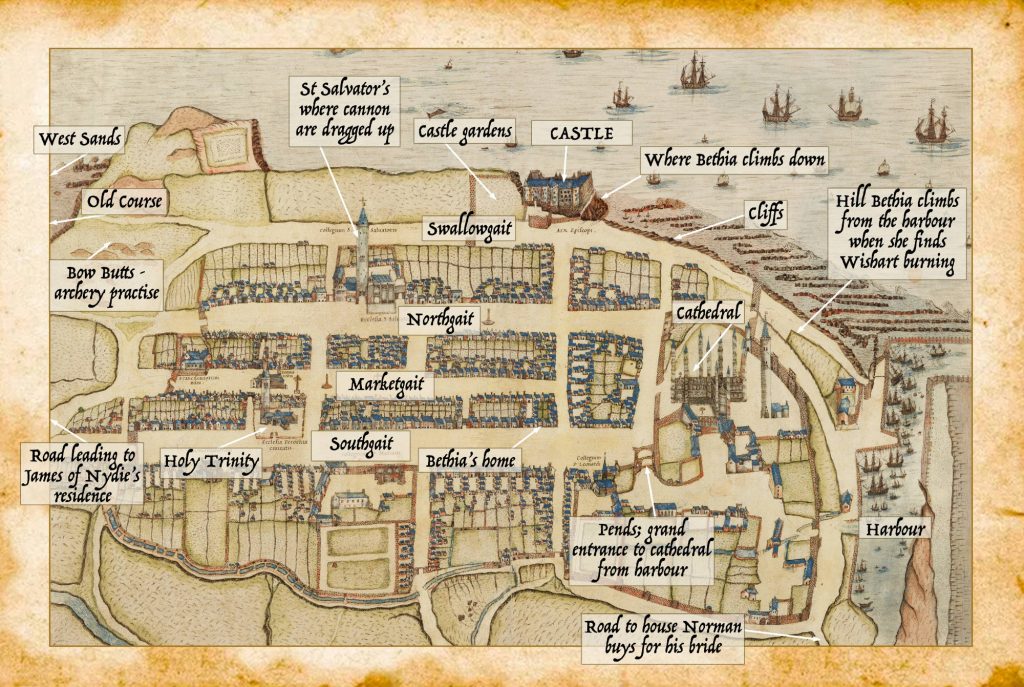

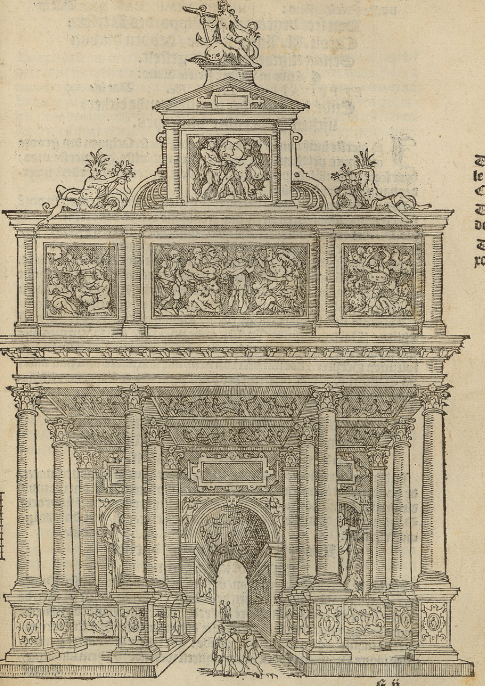

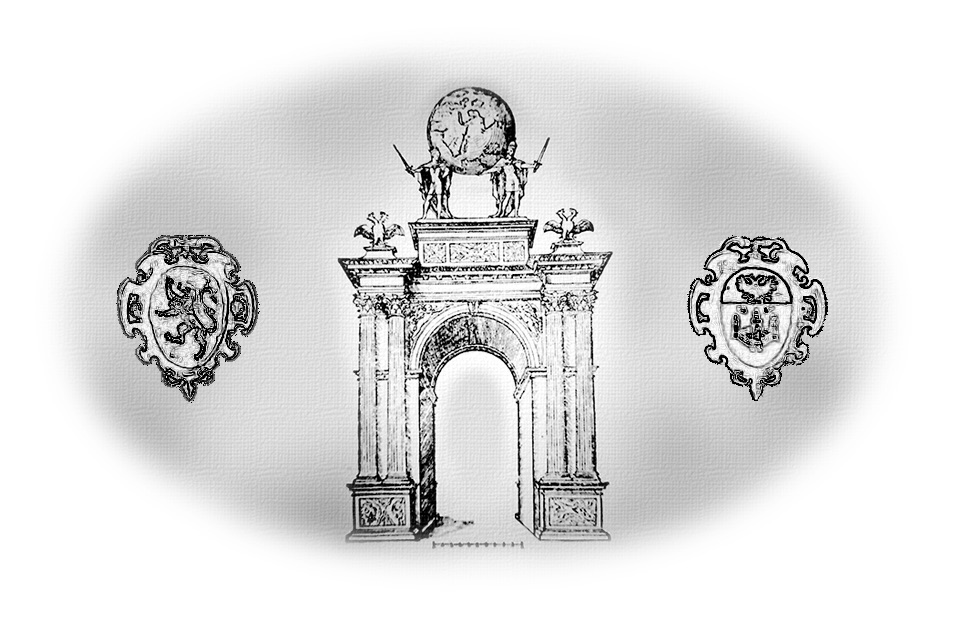

There are men working even though the sun is long set. The curfew has been relaxed, for the city must work night and day to complete the preparations in time. Many have stripped to the waist, and the torchlight plays across their skin. There’s something otherworldly about watching them swarming over the structures like large fiery devils. The designer, moves anxiously among them, regularly calling out for them to take care.

‘And this is only one of many that van Aelst is overseeing,’ Mainard says. ‘Come, I would take you to the gate through which Charles and Philip will enter.’

They pass beneath a triumphal arch and Bethia stands in its centre looking up. ‘It’s like a temple.’

Mainard nods enthusiastically. ‘Good, it is indeed – the design is inspired by the Temple of Janus. And see how they have used the colossi to look as though they are supporting the whole structure. It’s the story of Antwerp; our wealth and industry is a foundation for the emperor’s greatness. But I want to show you the German arch.’

Bethia stands before it, amazed. The white marble of the double arch glows ghostly in the night. Beneath the arch, tall niches have been carved. She points. ‘What is to go here?’

‘Golden statutes, one of Charles and one of Philip, will be lowered into place closer to the day, for they will need guarding.

Bethia stares up at the inscriptions already carved above the niches. Mainard borrows a torch from a sconce, ignoring the men at work who grumble at the withdrawal of their light.

‘Immortalis fama,’ she reads. ‘I suppose that refers to the emperor and his son. Their fame will never die.’

‘And Disciplina,’ says Mainard, waving his hand to the other inscription. ‘Learning and Immortal Fame – the perfect combination.’

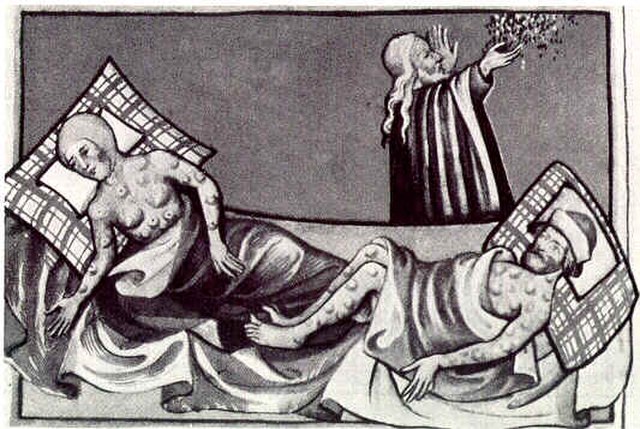

But not everyone is happy and there is much grumbling about the money being spent. When the event is disrupted by a thunderstorm it’s seen as an ill omen and a sign that God also disapproved of the excessive nature of the celebrations.

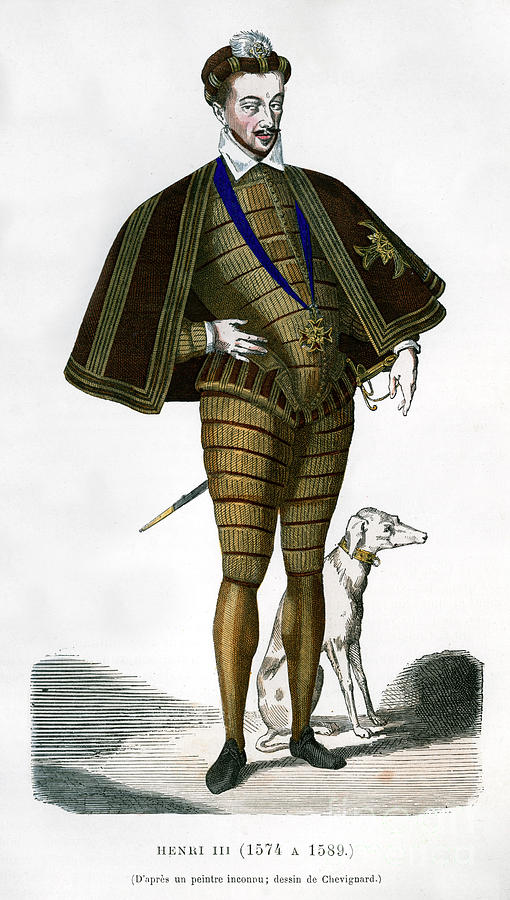

In the current work-in-progress my character Will gets caught up in the siege of Rouen. Doing some research I came across a wonderful description of King Henri II’s royal entry to Rouen as part of his Grand Tour in 1550. ‘Its citizens were determined that in case mythology and symbolism had lost their pristine charms, an absolutely novel entertainment should be given to the King on this occasion. So on the fields between the Couvent des Emmurées and the left bank of the Seine a great sham fight was arranged between a number of Norman sailors and fifty of the newly discovered tribe of Tupinambas from Brazil (where the sailors had been trading) , clad only in their own skins and a few stripes of paint.’

Apparently the novel entertainment was well received by the ladies of the party which included Henri II’s wife, Catherine de Médici and his mistress Diane de Poitiers. The king displayed Diane’s crescent throughout and one cannot but sympathise with Catherine de Medici for the endless public humiliations she had to impassively endure.

The king was also accompanied at Rouen by Marie of Guise, Queen-Dowager of Scotland, who was on a short visit to France to be with her daughter the future Mary, Queen of Scots. Mary was only eight years old and hadn’t seen her mother since she was sent to France aged five (the treacherous journey is described in The Conversos) to escape from England’s Rough Wooing. This visit was the last time she would ever see her mother, who died shortly before Mary returned to Scotland ten years later.

References:

Mark A. Meadow, “Met geschickter ordenen”: The Rhetoric of Place in Philip II’s 1549 Antwerp “Blijde Incompst”

Christophe Schellekens, The Antwerp Joyous Entry of 1549 The Florentine-Genoese conflict as a window on the role of a trading nation in political cultural transfers

USA: here

Canada: here

UK: here